Most weight-loss advice still treats your body like a spreadsheet: eat less, move more, and the number on the scale will obey. That model works for about two weeks—right up until it doesn’t.

If you’ve ever lost 5–10 pounds quickly and then felt your appetite turn feral, your sleep get worse, your energy tank, and the weight rebound like a rubber band, you didn’t “lose discipline.” You ran into a biological system designed to protect you: your weight set-point.

Weight loss isn’t just about burning fat. It’s about convincing your brain you’re safe while you do it.

Key takeaways

- Your body defends a range of weight (set-point/set-range) using hunger, cravings, and energy expenditure—not willpower.

- Crash dieting triggers a predictable defense: lower leptin, higher hunger signals, and reduced daily movement (NEAT).

- The biggest hidden lever is not gym workouts—it’s non-exercise activity (steps, fidgeting, posture), which your brain can quietly “turn down.”

- Sustainable fat loss often requires a slow deficit + strength training + diet breaks to prevent set-point rebound.

- The goal is not “perfect dieting.” The goal is a repeatable system that keeps performance, sleep, and mood stable while fat drops.

First, define the enemy: the “thermostat,” not the furnace

People often picture metabolism like a furnace: if you add less fuel (food), the fire must shrink. But human biology behaves more like a thermostat: when the room gets colder, the system turns on heaters and closes windows. Your body adjusts.

The set-point idea is simple: your brain has a preferred energy reserve level. If weight drops too fast or too far, your body doesn’t celebrate—it defends. It raises appetite and reduces output to push you back to “normal.”

In real life, the body typically defends a range rather than a single number. That’s good news. It means you can shift the range over time. The bad news: when you diet aggressively, you often trigger defense mechanisms that lock the range in place—or push it upward after repeated rebounds.

The three levers your brain uses to fight your diet

When calories drop, your brain doesn’t just “let fat go.” It uses three major levers to protect energy stores. Understanding them makes the process feel less mysterious—and far more controllable.

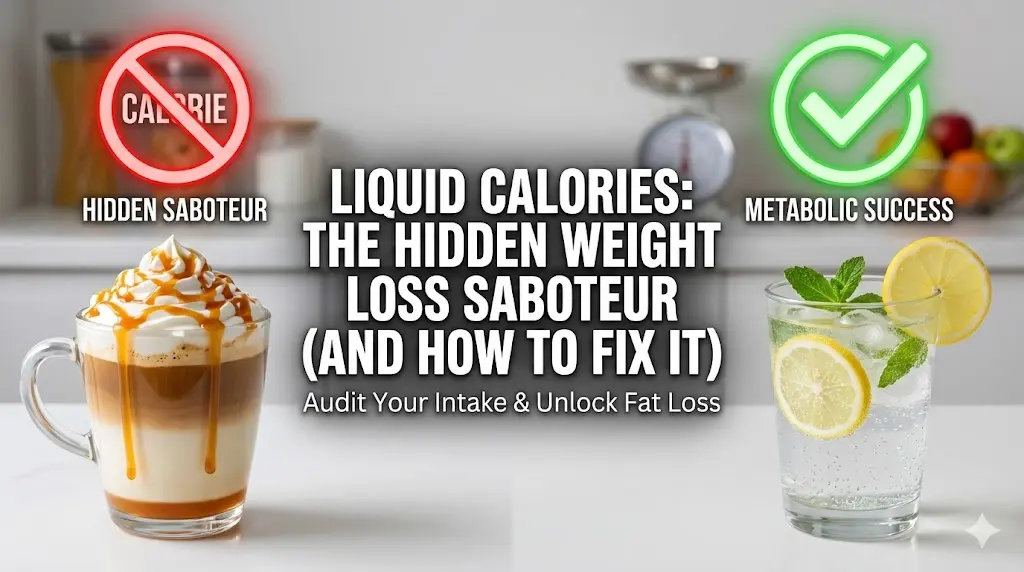

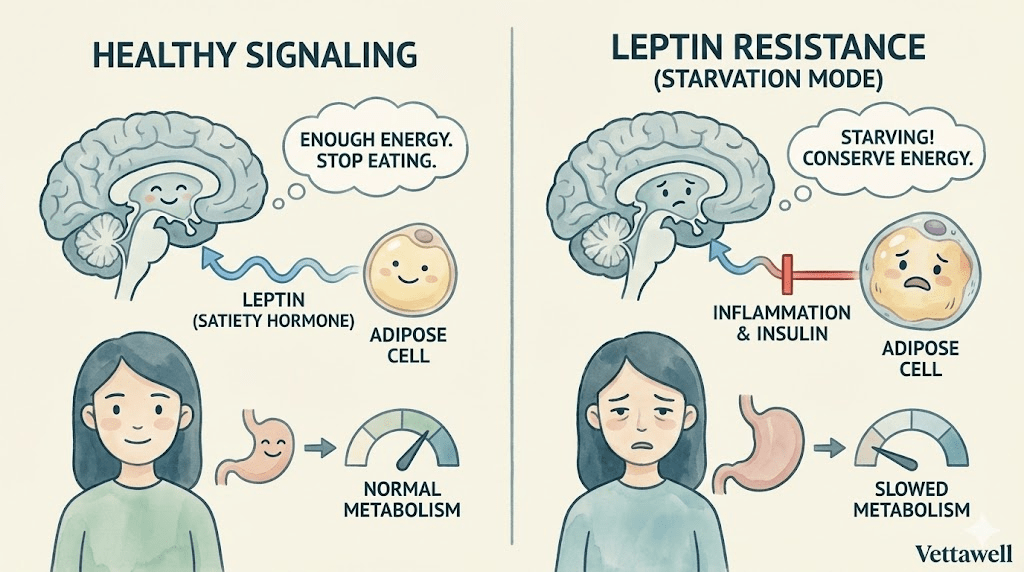

Appetite is the obvious defense: more hunger, more cravings, and louder food thoughts. This is not weakness. It’s your brain interpreting weight loss as risk.

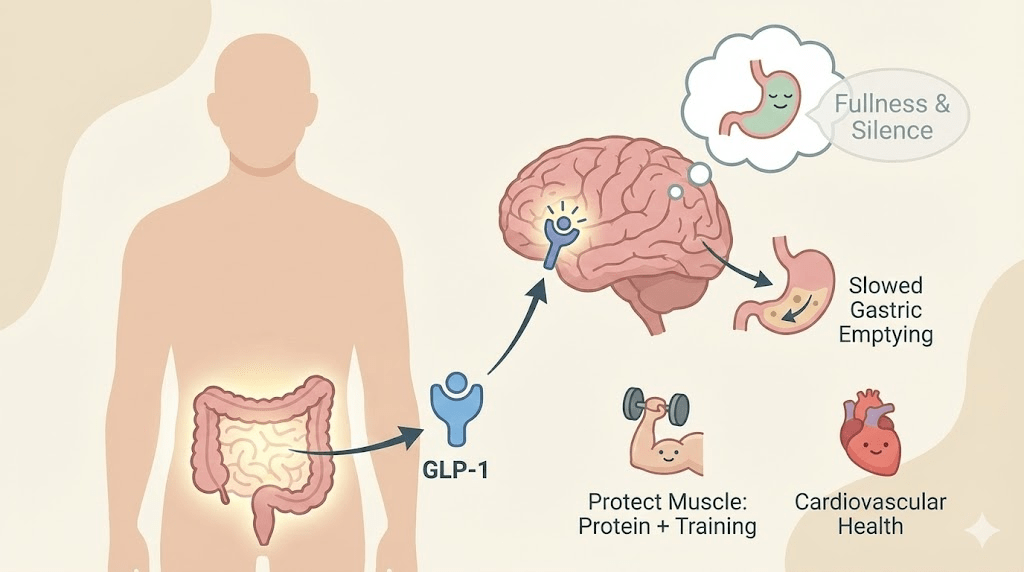

- Leptin drops: Leptin is produced by fat tissue and signals energy availability. As fat mass and intake fall, leptin falls—and hunger rises.

- Food salience increases: Food becomes more rewarding. You notice bakery smells, snack ads, and office treats more intensely.

- Craving specificity appears: Many people don’t just want “food.” They want quick energy—sugary, fatty, hyper-palatable options.

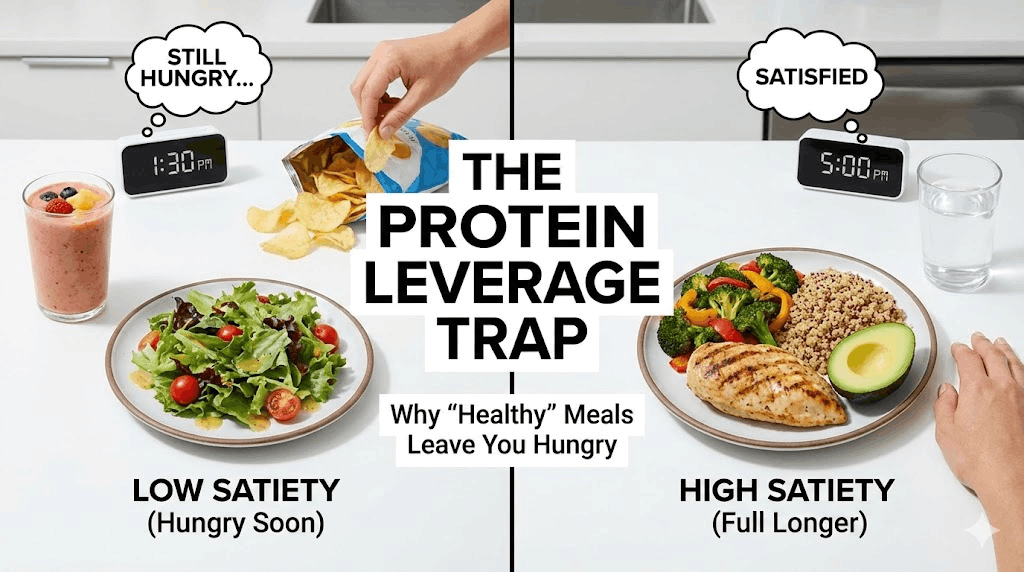

Your body can reduce total energy output without you noticing. The most important mechanism here is NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis): the calories you burn through daily movement that isn’t deliberate exercise.

- You sit more. You stand less. You take fewer stairs.

- You fidget less. You gesture less. You move your feet less.

- You subconsciously choose shorter routes and avoid unnecessary movement.

Many people “keep training” while their body quietly deletes 3,000–6,000 steps per day. The deficit vanishes without a single cheat meal.

Stress doesn’t “break” weight loss via magic. It breaks it through predictable pathways: worse sleep, higher cravings, more inflammation, and more emotional eating. Dieting itself can be a stressor—especially when paired with intense training, low carbs, and high caffeine.

- Sleep restriction increases hunger signals and reduces impulse control.

- Chronic cortisol elevation can increase appetite and make high-reward foods harder to resist.

- Recovery debt makes training feel harder, which reduces adherence and increases compensatory snacking.

Why crash diets “work” fast—and then collapse

Crash diets succeed short-term because they create a large deficit quickly. But they usually fail because they trigger every defense lever at once: leptin drops hard, NEAT collapses, training output suffers, and hunger becomes obsessive.

What looks like a “plateau” is often a compensated deficit: you’re eating less, but your body is also burning less. The scale stops, frustration rises, and then the rebound begins when the diet becomes unbearable.

Yes, glycogen and water fluctuate. But post-diet regain is frequently driven by a real behavioral-physiology loop: hunger stays elevated for weeks, food becomes hyper-rewarding, and activity stays suppressed until energy availability feels safe again.

The set-point lowering protocol

Lowering your set-range is a project, not a 10-day sprint. The strategy is to create fat loss while keeping the brain’s threat alarms low. That requires controlling the size of the deficit, protecting muscle, and maintaining movement.

The most sustainable deficit is often the least exciting: small enough to preserve sleep, mood, and training performance. A common target is a moderate deficit that produces slow, steady loss rather than weekly chaos.

- If you’re losing faster than you can sustain, you’re not winning—you’re borrowing from the rebound.

- Aim to keep hunger manageable (not absent), and keep training performance stable.

- If you’re thinking about food all day, the deficit is too aggressive.

Your body can lose weight by losing fat, muscle, or both. The scale doesn’t care. Your metabolism does. Losing muscle reduces your energy buffer and makes maintenance harder.

- Protein floor: Build every meal around protein first.

- Strength training: A minimum effective dose of progressive resistance is a muscle-preserving signal.

- Recovery: Poor sleep and excessive training volume increase muscle loss risk in a deficit.

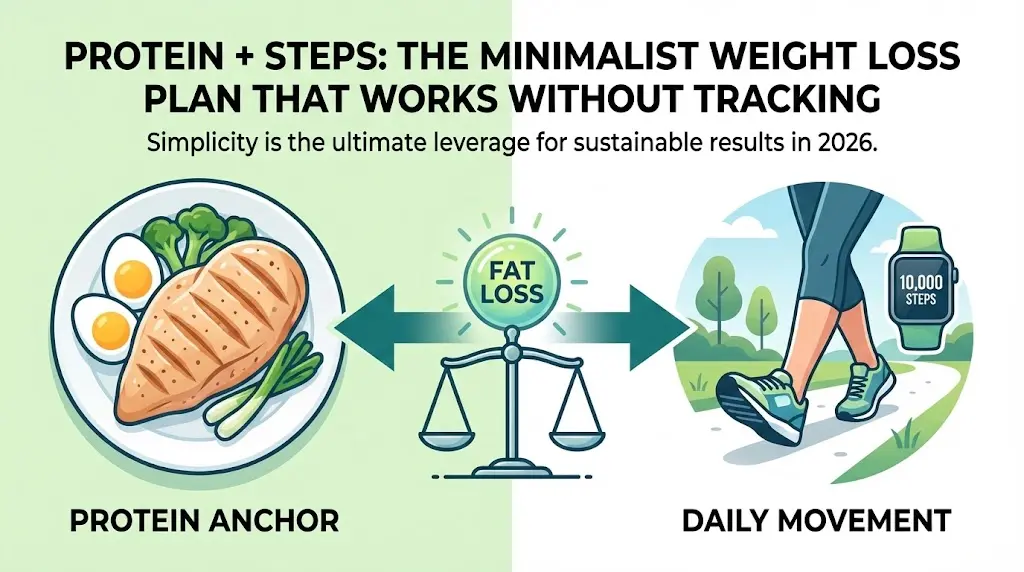

Most diets fail because NEAT silently drops. The simplest countermeasure is embarrassingly practical: walk. Not for calorie burn alone, but to prevent your brain from turning off movement.

- Set a step minimum (not an aspirational goal).

- Anchor it to routine: a morning walk, a post-lunch walk, and a post-dinner walk.

- If you train hard, do not assume it replaces steps—many people reduce steps after hard workouts.

The best fat-loss cardio is the one that doesn’t increase your appetite or wreck your recovery.

A diet break is not a cheat week. It’s a planned return to maintenance calories for a short period to stabilize hunger, training performance, and adherence. For many people, it’s what prevents the all-or-nothing collapse.

- Use breaks when hunger becomes loud, sleep worsens, or training performance declines.

- Keep protein high and keep steps stable—don’t turn a break into a binge.

- Think of breaks as pressure valves that keep the overall system sustainable.

If you want a smaller appetite without fighting your brain, build meals that increase satiety per calorie. The pattern is consistent: protein + fiber + volume + minimal ultra-processed triggers.

- Protein: eggs, fish, lean meat, Greek yogurt, tofu, legumes.

- Fiber/volume: vegetables, berries, beans, soups, salads with real protein.

- Fats: enough for satisfaction, not so much they dominate calories.

- Trigger audit: if a food reliably causes loss of control, it’s not a “moderation” food—at least not during a cut.

A practical 6-week framework

If you want a simple template, here is a structure many people can execute without obsessing. Adjust based on your baseline, preferences, and medical context.

- Weeks 1–2 (Stabilize): Keep meals consistent. Hit protein at each meal. Establish a step minimum. Do not change everything at once.

- Weeks 3–4 (Cut): Create a moderate deficit. Keep strength training. Add a 10–15 minute walk after the largest meal.

- Week 5 (Hold): Return to maintenance for 5–7 days. Keep protein and steps. Let hunger and performance normalize.

- Week 6 (Cut again): Resume the moderate deficit. Compare adherence, sleep, and cravings to Weeks 3–4.

How to know you’re lowering your set-range (not just white-knuckling)

The best sign is not the scale. The best sign is that weight loss begins to feel less dramatic over time. You can miss a meal without panic. You can be around food without obsession. You can maintain results without a sense of constant deprivation.

- You can maintain weight without rigid rules or daily stress.

- Your step count stays stable even while dieting.

- Your sleep is not collapsing.

- Cravings are present but not controlling.

- You feel “normal” most days—just slightly hungry sometimes.

Common pitfalls

- Dieting aggressively while also increasing training volume (double stress).

- Ignoring NEAT: assuming gym workouts automatically create a deficit.

- Under-eating protein and losing muscle (then blaming “metabolism”).

- Using ultra-processed “diet foods” that keep cravings alive.

- Skipping sleep hygiene and trying to fix fatigue with caffeine.

Practical next steps

- Pick a step minimum you can hit on bad days and track it for 14 days.

- Make protein the first decision: 25–40g per meal as a default target (adjust as needed).

- Strength train 2–4x/week and keep cardio “low-cost” (walking, zone 2).

- Use a planned 5–7 day maintenance week every 3–6 weeks if hunger or sleep deteriorates.

- If you have a history of disordered eating, work with a qualified clinician before dieting.

Quick checklist

- Protein shows up at every meal.

- Steps are stable week to week (not collapsing).

- Strength training is scheduled (not optional).

- Sleep opportunity is 7–9 hours most nights.

- The deficit is “boring” enough to repeat.

Important note: This article is educational and not medical advice. If you have metabolic disease, are pregnant/postpartum, or take medications that affect appetite or glucose, consult a qualified healthcare professional to individualize your plan.