GLP‑1 medications (like semaglutide and tirzepatide) were the first weight-loss tools in decades that felt like turning off the food noise instead of fighting it with willpower. For many people, the scale finally moved, cravings finally quieted, and “portion control” stopped being a daily war.

Then comes the hard question: what happens when you stop? The uncomfortable truth is that many people don’t regain weight because they’re weak—they regain because biology rebounds. Hunger signals return, energy expenditure drops, and the habits you didn’t need on the medication suddenly become non‑negotiable.

GLP‑1s are a powerful lever. But the long-term outcome depends on what you build while the lever is working.

Key takeaways

- The most common driver of post‑GLP‑1 regain is not “bad discipline,” it’s the appetite + muscle equation (higher hunger + lower lean mass).

- If you lose weight quickly, you risk losing lean mass; losing muscle lowers resting energy needs and makes regain easier.

- Your goal on GLP‑1 is not just “smaller.” It’s metabolically safer: protect muscle, stabilize habits, and repair your food environment.

- The best off‑ramp is typically gradual and clinician‑guided (dose spacing or step‑downs), paired with a structured lifestyle transition.

- Maintenance is a system: protein floor + strength training + daily movement + sleep + a relapse plan.

First: what GLP‑1s actually do (and what they don’t)

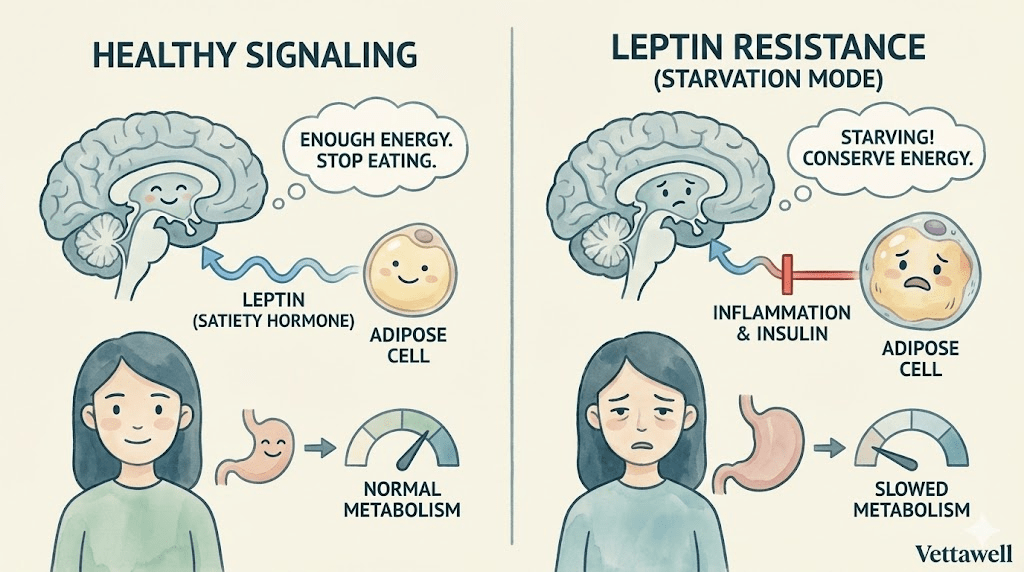

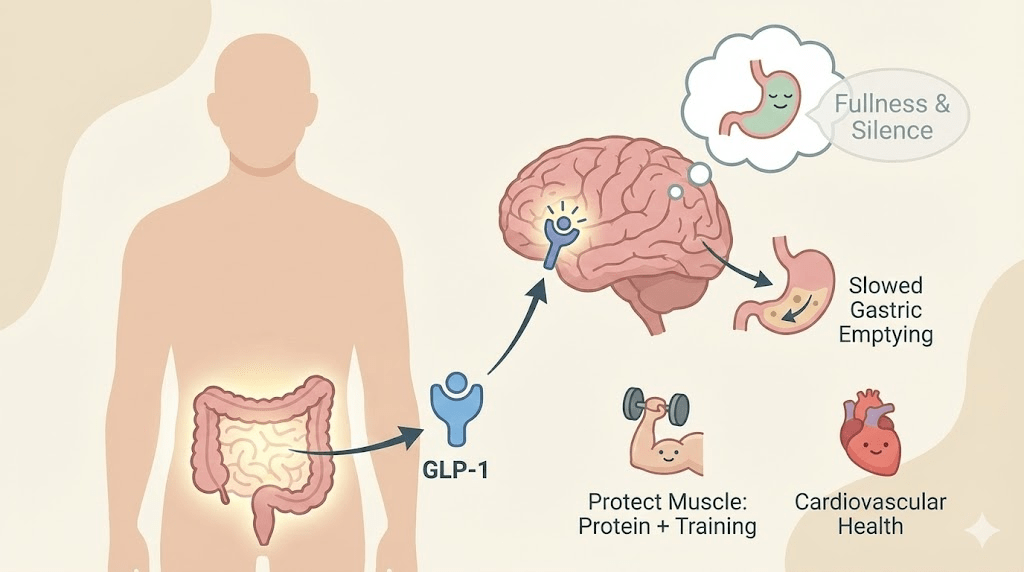

GLP‑1 receptor agonists and related incretin therapies work through multiple pathways: they enhance satiety signaling, reduce appetite, slow gastric emptying in many users (especially early), and improve glycemic regulation. The lived experience is usually simple: you feel full sooner and think about food less.

But GLP‑1s do not automatically build muscle, fix sleep debt, correct stress eating triggers, or redesign the home food environment. Those are the pieces that determine what happens when the medication is reduced or stopped.

Why regain happens after stopping (the three predictable rebounds)

On the medication, many people unintentionally under-train the skills that matter most for maintenance: meal structure, protein planning, “boring” food prep, and hunger management. When the appetite signal returns, it can feel like a sudden personality change—when it’s really a medication effect disappearing.

Rapid weight loss commonly reduces non‑exercise activity (NEAT): fewer steps, less fidgeting, less spontaneous movement. Add lower body mass and often lower calorie intake, and total energy expenditure tends to decline. If you don’t deliberately rebuild movement, maintenance becomes mathematically harder.

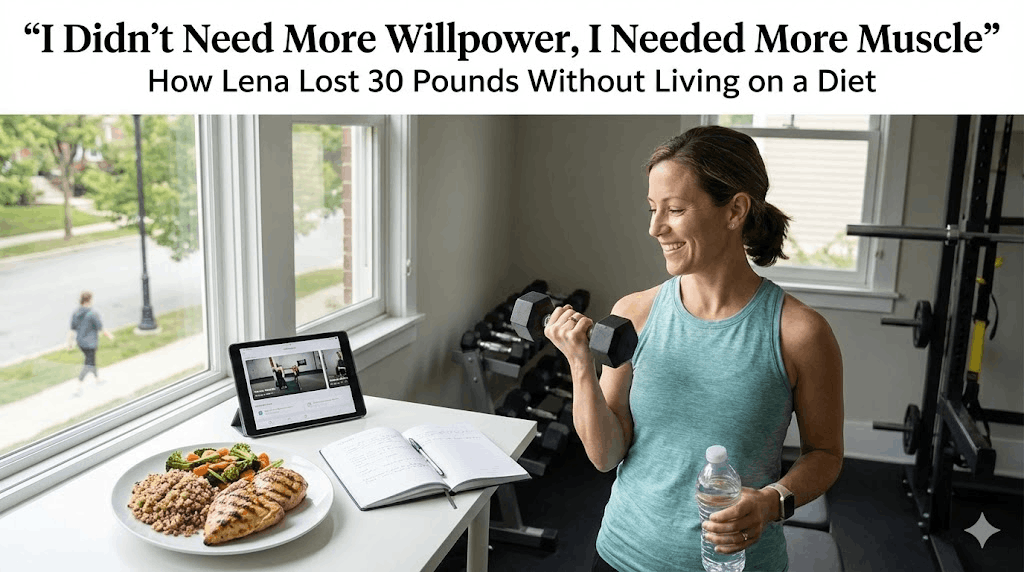

When appetite is suppressed, it’s easy to miss protein targets and hard to lift heavy consistently. That combination increases the risk of losing lean mass. Muscle is not just for aesthetics—it’s the tissue that buffers glucose, supports strength, and raises your energy budget. Less muscle means you can maintain less food without regaining.

If your body becomes a smaller engine, it requires less fuel. If your appetite returns to the old level, the math flips fast.

The Off‑Ramp Blueprint: 4 pillars that prevent rebound

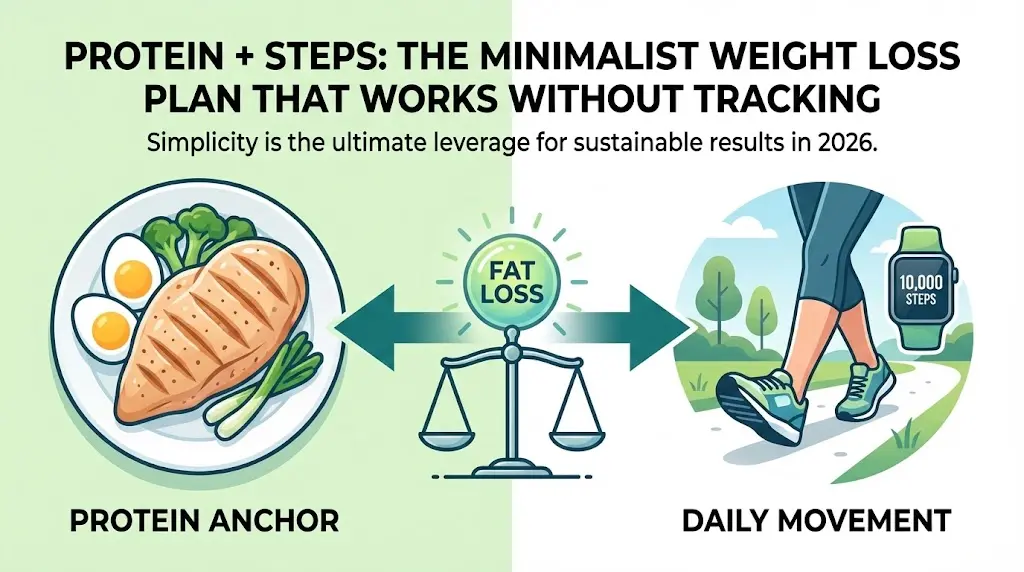

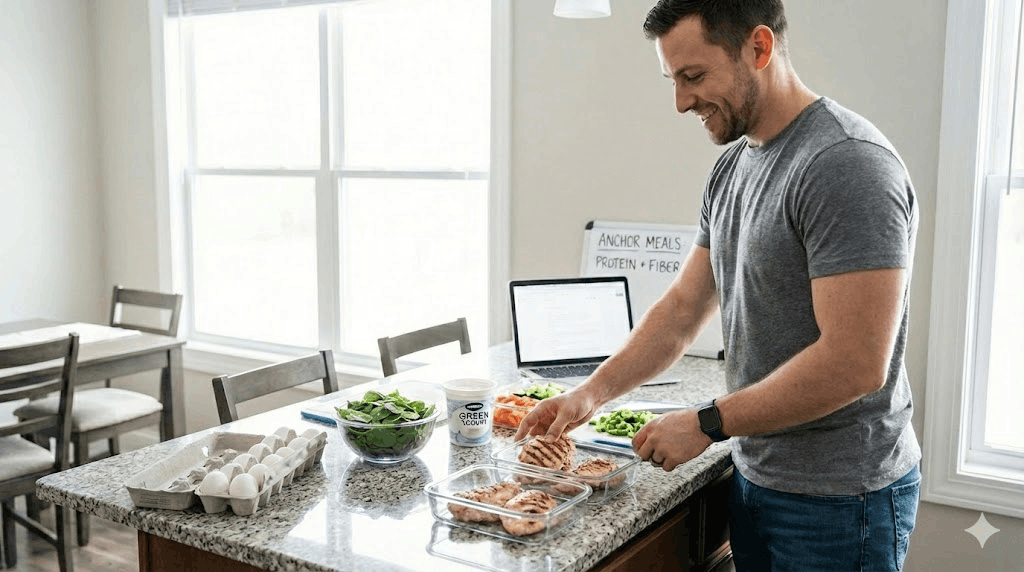

If you do nothing else, do this: establish a minimum daily protein target that you can hit even when appetite is low. This protects muscle and increases satiety per calorie.

- Rule of thumb: 1.6 g/kg/day of goal body weight is a strong target for many active adults (adjust with a clinician if you have kidney disease or other constraints).

- If that number feels too high: set a minimum “protein floor” (for example: 25–40 g per meal, 2–3 times/day).

- Make it frictionless: keep 2–3 default proteins available (Greek yogurt, eggs, chicken, tofu, fish, protein shakes).

- Don’t wait for hunger: when you’re on GLP‑1, protein is a scheduled medicine, not an intuitive craving.

The off‑ramp period is when strength training pays the highest dividend. You’re trying to preserve (or rebuild) lean mass so that maintenance calories don’t crash.

- Frequency: 2–4 sessions/week.

- Focus: compound patterns (squat/hinge/push/pull/carry).

- Progression: add reps or load slowly; don’t chase soreness.

- If energy is low: keep the session short but keep the habit (20–35 minutes still works).

If you’re new to lifting, the best plan is the one you’ll actually do: machines are fine. The goal is stimulus, not perfection.

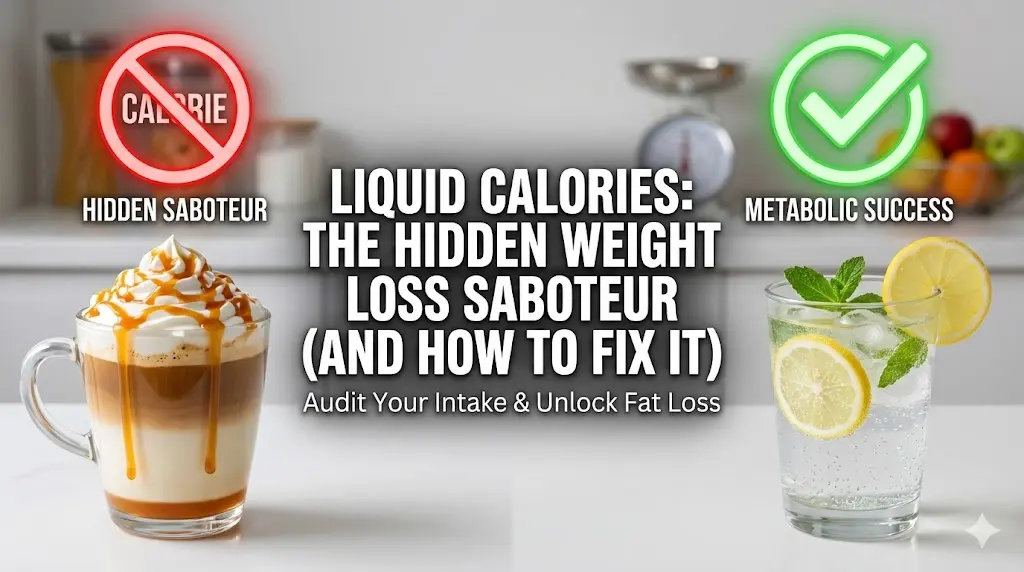

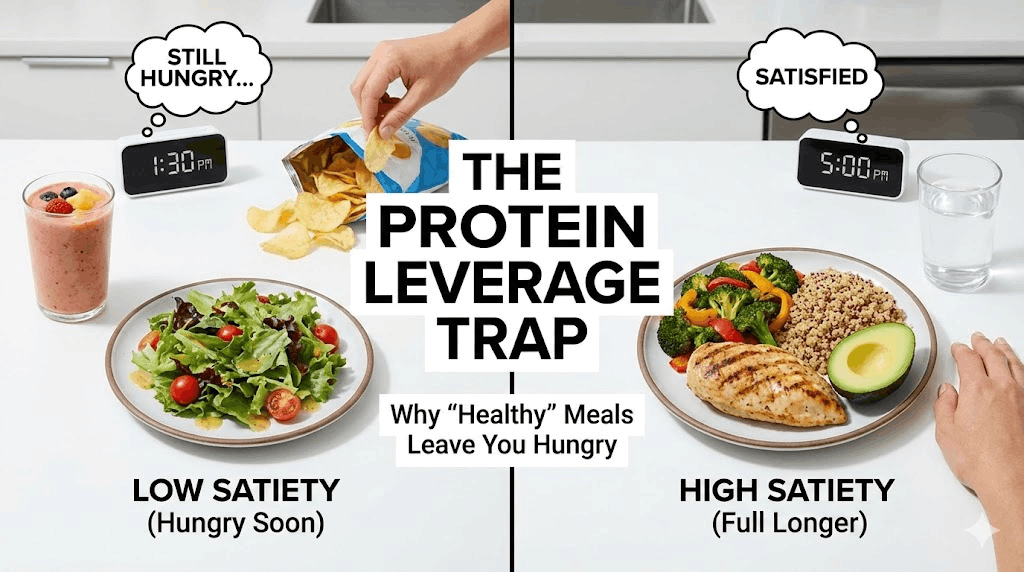

When medication support decreases, you want meals that are physically large, slower to digest, and stable for blood sugar. This reduces the sensation that you’re “white‑knuckling” hunger.

- Volume foods: vegetables, broth-based soups, berries, potatoes (especially cooled/reheated), legumes.

- Fiber anchors: beans/lentils, chia/flax, oats (if tolerated), psyllium, cruciferous vegetables.

- Protein first: start the meal with protein + fiber before starches and sweets.

- Liquid calories audit: alcohol, sugary coffee drinks, juices—these bypass satiety fast.

Maintenance is less about eating less and more about eating in a way that your brain accepts as “enough.”

The off‑ramp is where many people fail because they treat early regain as a moral crisis instead of a feedback signal. You need a plan you execute automatically.

- Trigger: scale trend up for 2–3 weeks or appetite feels unmanageable for 10+ days.

- Reset: return to baseline structure for 14 days (protein floor, strength x2–3/week, 8–10k steps/day, fiber anchor at lunch/dinner).

- Escalate: if still worsening, discuss options with your prescribing clinician (dose adjustment, spacing strategy, or other medical evaluation).

The taper conversation: what “off‑ramp” can look like

Medication changes must be clinician‑guided. In general practice, “off‑ramp” approaches can include dose step‑downs, dose spacing (e.g., extending the interval), or maintenance at the lowest effective dose—depending on risk profile, prior weight history, and side effects.

Your job is to arrive at that taper with the right foundations already built. If you wait until the medication stops to build the system, it’s like trying to install seatbelts after the crash.

A practical 12‑week transition plan (built for real life)

- Hit the protein floor daily (track for accuracy—app or checklist).

- Strength train 2–3x/week (full body).

- Set a step baseline (start where you are; add 1,000 steps/week until you reach a sustainable target).

- Solve the predictable GLP‑1 friction points: hydration, constipation prevention, and meal scheduling.

- Choose 2 default breakfasts and 3 default lunches you can repeat.

- Add a fiber anchor to lunch and dinner (legumes or a large salad + protein).

- Practice “planned flexibility”: one restaurant meal/week, but decide your protein and vegetables first.

- Audit liquid calories and alcohol; treat them as optional, not routine.

- Introduce one higher‑calorie day/week (still protein‑anchored) to practice real‑world maintenance.

- Strength train 3–4x/week if feasible; otherwise keep 2–3 and add light conditioning.

- Create your relapse protocol document (what you do if weight trends up).

- Discuss taper/spacing with your clinician only after your routine feels stable.

Side effects and safety signals to take seriously

GLP‑1 medications can cause side effects and complications in some users. If you’re using them, safety is part of the protocol—not an afterthought.

- Persistent vomiting, severe abdominal pain, or dehydration: seek medical care promptly.

- Constipation: common—support with fluids, fiber, and clinician‑approved strategies.

- Rapid weight loss without resistance training: higher risk of lean-mass loss; adjust your plan early.

- Mental health changes: appetite suppression can sometimes interact with mood, anxiety, or disordered eating patterns—flag this early with a professional.

If your plan relies on enduring side effects, it is not a sustainable plan.

Common pitfalls (why “I did everything right” still fails)

- Treating GLP‑1 as the plan instead of the tool—no strength training, no protein system, no environment changes.

- Losing weight fast, then trying to “maintain” on the same low intake with a now‑smaller energy budget.

- Stopping abruptly without a transition structure (food noise returns; the old environment wins).

- Skipping breakfast and protein early, then overeating at night once appetite rebounds.

- Confusing scale fluctuations (salt, glycogen, constipation) with true fat regain—then making drastic, chaotic changes.

Practical next steps

- Define your protein floor and set default meals that hit it reliably.

- Schedule strength training like a prescription: 2–4 sessions/week for the next 12 weeks.

- Set a daily movement baseline (steps) and increase gradually; don’t rely on “big workouts” alone.

- Create a written relapse protocol and share it with your clinician or coach.

- If you are considering tapering, plan the taper around your routine—not the other way around.

Quick checklist

- I hit my protein floor most days (or I know exactly why I didn’t).

- I strength train at least 2x/week (minimum effective dose).

- I have a default meal structure for busy days.

- My steps/movement baseline is stable week to week.

- I have an off‑ramp plan with a clinician, and a relapse plan for myself.

Important note: This article is educational and not medical advice. GLP‑1 medications require individualized clinical supervision. If you have severe side effects, rapid unintended weight loss, or significant mood changes, seek professional care.