In 1994, obesity research changed overnight with the discovery of leptin—a hormone that exposed a hidden truth: body fat isn’t just stored energy. It’s an endocrine organ that sends real-time messages to your brain about how much fuel you have on board.

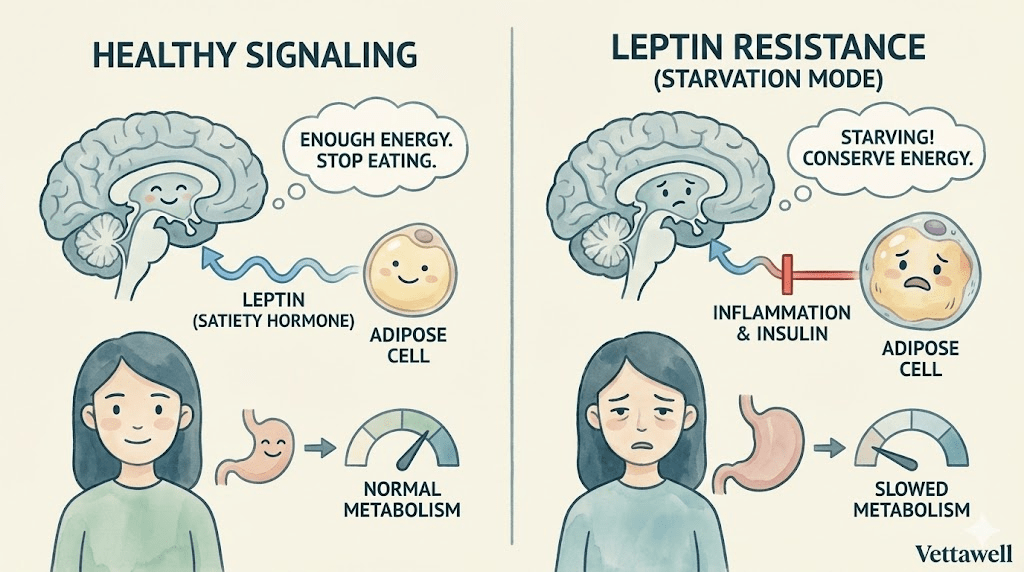

In an ideal system, leptin works like a dashboard gauge. As fat stores rise, leptin rises, the brain receives the signal, hunger eases, and energy expenditure stays steady. In other words: “We’re stocked up. You can stop searching for food.”

If your brain believes you’re running out of fuel, it will override your intentions—no matter what the mirror or the scale says.

Key takeaways

- Leptin is produced by fat cells and signals the hypothalamus about energy reserves and satiety.

- Many people with higher body fat have high leptin—but the brain responds poorly due to leptin resistance.

- Leptin resistance can make the body behave as if it’s in starvation mode: more hunger, lower energy, and reduced spontaneous movement.

- Inflammation, chronically high insulin, high triglycerides, poor sleep, and ultra-processed diets may contribute to impaired signaling.

- You don’t “add more leptin” to fix the problem; you focus on resensitizing the system through lifestyle and metabolic health.

What leptin actually does

Leptin is often called the “satiety hormone,” but that label is too narrow. Think of leptin as a long-term energy status signal—a message to your brain about whether your body can afford to burn energy freely or needs to conserve.

The signal is primarily processed in the hypothalamus, a region that coordinates hunger, metabolism, temperature regulation, and many survival behaviors. When leptin signaling works well, it supports a stable appetite and a stable metabolic rate.

- More fat stored → more leptin → brain senses plenty → appetite decreases

- Less fat stored → less leptin → brain senses scarcity → appetite increases

The paradox of obesity

At first glance, leptin seems like it should solve obesity by itself. If fat cells make leptin, then people with more fat should have more leptin—and therefore feel less hungry. In many cases, they do have 3–4x higher leptin than average.

So why doesn’t appetite simply switch off? The common answer is leptin resistance: the signal is present, but the brain responds as if it isn’t.

It’s not always a leptin shortage. It’s often a leptin signal problem.

What leptin resistance feels like in real life

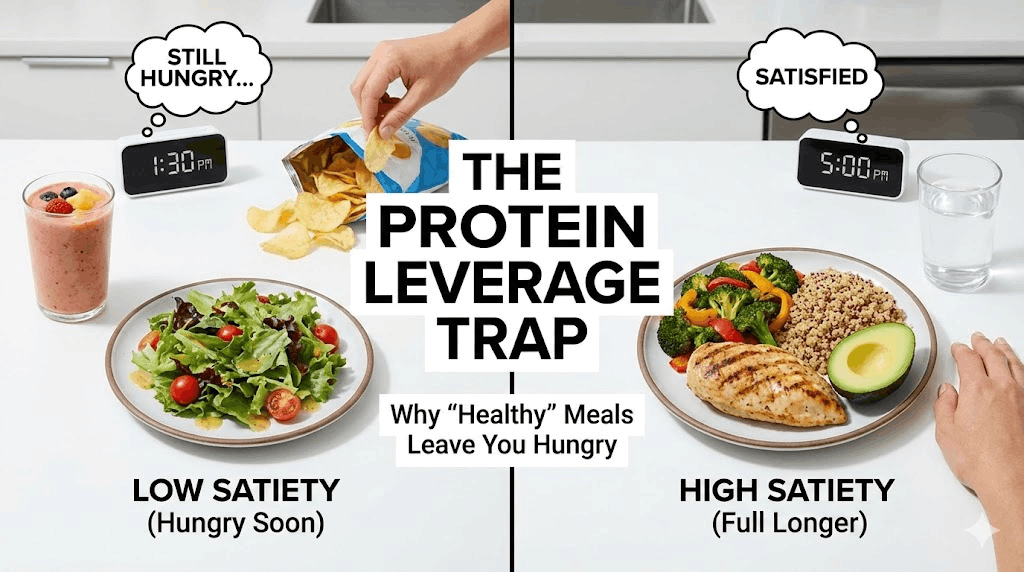

Leptin resistance can look like “willpower failure,” but physiologically it can feel like a chronic mismatch between effort and outcome. Many people describe some version of: hungry soon after eating, cravings that feel unusually loud, low drive to move, and weight regain after restrictive dieting.

When the hypothalamus can’t read leptin correctly, it may interpret the body as energy-depleted—even when there is abundant stored fat. That perceived scarcity triggers protective responses designed to keep you alive.

- Voracious hunger: appetite signals ramp up, cravings intensify, and food becomes harder to ignore.

- Energy conservation: thyroid signaling and resting metabolic rate may downshift, making weight loss slower than expected.

- Lower NEAT: NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis) tends to drop—less fidgeting, fewer steps, less spontaneous movement.

- More “food salience”: the brain prioritizes seeking food, making dieting feel like mental noise and obsession.

What breaks the signal

Leptin resistance is not usually caused by one single factor. It’s more like a network issue. Researchers have proposed multiple contributors that can interfere with how leptin is transported, received, or interpreted—especially in the hypothalamus.

- Inflammation in the hypothalamus: inflammatory signaling can disrupt appetite regulation and hormone sensitivity.

- Chronically elevated insulin: high insulin states often travel with leptin resistance and may impair normal satiety signaling.

- High triglycerides: elevated blood fats may interfere with leptin transport across the blood–brain barrier in some models.

- Ultra-processed diets: highly refined carbohydrates and inflammatory fat profiles can worsen metabolic dysfunction.

- Sleep deprivation: poor sleep dysregulates hunger hormones and increases inflammatory tone, amplifying appetite.

A key insight: when your metabolism is inflamed and dysregulated, the body may treat weight loss attempts as threat signals—driving stronger compensation (more hunger, less energy).

Why "eat less, move more" becomes torture

If leptin resistance is present, cutting calories harder can backfire psychologically and physiologically. You’re not just reducing intake—you’re triggering the brain’s scarcity alarms. Over time, hunger rises and energy drops, and the strategy becomes harder to sustain.

This doesn’t mean energy balance is fake. It means that the experience of calorie restriction differs dramatically depending on hormonal signaling. For one person, a deficit feels manageable. For another, it feels like fighting a brain that thinks it’s dying.

Can you take a leptin pill?

For most people with obesity, leptin is already high—so simply adding more leptin doesn’t solve the problem. In rare genetic leptin-deficiency cases, leptin replacement can be transformative, but that’s not the common scenario.

The practical goal is not “more leptin.” The goal is better leptin sensitivity.

Reversing the resistance: resensitize the system

Improving leptin sensitivity is less about one magic trick and more about building an environment where the brain trusts the signal again: lower inflammation, more stable blood sugar, better sleep, and stronger muscle-based metabolism.

- Prioritize sleep first. Short sleep increases hunger signaling and makes appetite louder the next day. Treat sleep as metabolic therapy, not a luxury.

- Reduce ultra-processed carbohydrates. Focus on fiber-rich, minimally processed foods to stabilize insulin and appetite.

- Hit a protein floor. Protein increases satiety and helps preserve lean mass during fat loss—crucial for long-term metabolic health.

- Lift weights (or do resistance training). Muscle improves glucose disposal and helps prevent metabolic slowdown from lean tissue loss.

- Increase daily movement. Steps and light activity improve insulin sensitivity without the stress load of constant high-intensity training.

- Address triglycerides and metabolic markers. If labs are elevated, the strategy should include nutrition, activity, sleep, and clinician-guided care.

If you want a short experiment that targets the signaling environment (without crash dieting), try two weeks of consistency:

- Keep a consistent wake time (±30–60 minutes).

- Eat protein at breakfast and lunch; include fiber at lunch and dinner.

- Walk 10 minutes after your largest meal.

- Do 2–3 resistance sessions (full-body basics).

- Reduce alcohol and late-night snacking to protect sleep depth.

Common pitfalls

- Cutting calories too aggressively and triggering rebound hunger and fatigue.

- Trying to outrun metabolic dysfunction with HIIT while sleep-deprived and under-fueled.

- Ignoring protein and strength work, leading to muscle loss and a slower metabolism.

- Relying on willpower strategies instead of changing the signal environment (sleep, food quality, stress).

- Assuming hunger equals weakness rather than data from your nervous system and hormones.

Practical next steps

- Prioritize protein at every meal to protect lean mass and reduce cravings.

- Build a sleep anchor: consistent wake time for 14 days.

- Replace one processed-carb snack per day with a fiber + protein option.

- Add 7,000–10,000 steps as a weekly average target (adjust for your baseline).

- If you suspect insulin resistance or have elevated triglycerides, consider lab review with a qualified clinician.

Quick checklist

- Sleep is 7+ hours when possible and wake time is consistent.

- Protein and fiber show up daily.

- Resistance training is scheduled (not optional).

- Daily movement exists beyond workouts.

- Processed foods are reduced more days than not.

Important note: This article is educational and not medical advice. If you have a medical condition or take medications that affect appetite or metabolism, consult a qualified healthcare professional.