In recent years, the world has been gripped by GLP‑1 fever. Drugs like semaglutide (brands include Ozempic for diabetes and Wegovy for weight management) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro for diabetes, Zepbound for weight management) have transcended clinical medicine and become a cultural phenomenon. The headlines tend to focus on “Hollywood weight loss,” but the deeper story is far more important: these medications have reshaped how clinicians think about obesity, appetite, and metabolism.

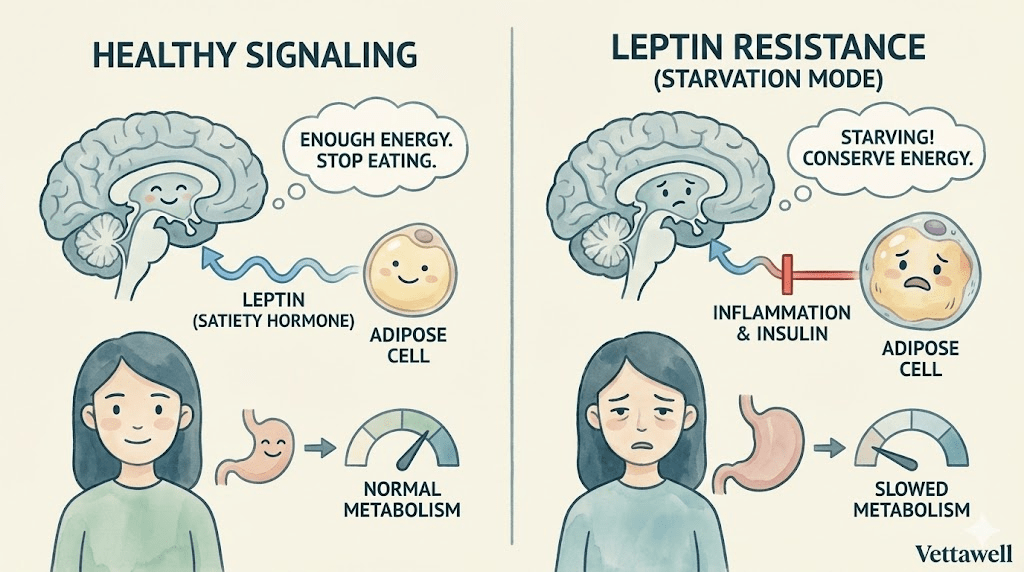

For decades, obesity was treated primarily as a behavioral failure—eat less, move more, try harder. GLP‑1 therapies challenge that framing. They highlight a different reality: for many people, body weight is strongly influenced by biology—hormones, appetite signaling, satiety, reward pathways, and the body’s defense against weight loss. This isn’t an argument that behavior doesn’t matter. It’s an argument that behavior sits on top of a system that can be dramatically harder for some bodies than others.

If hunger is driven by hormones and brain circuitry, “willpower” alone becomes a weak tool for a strong system.

Key takeaways

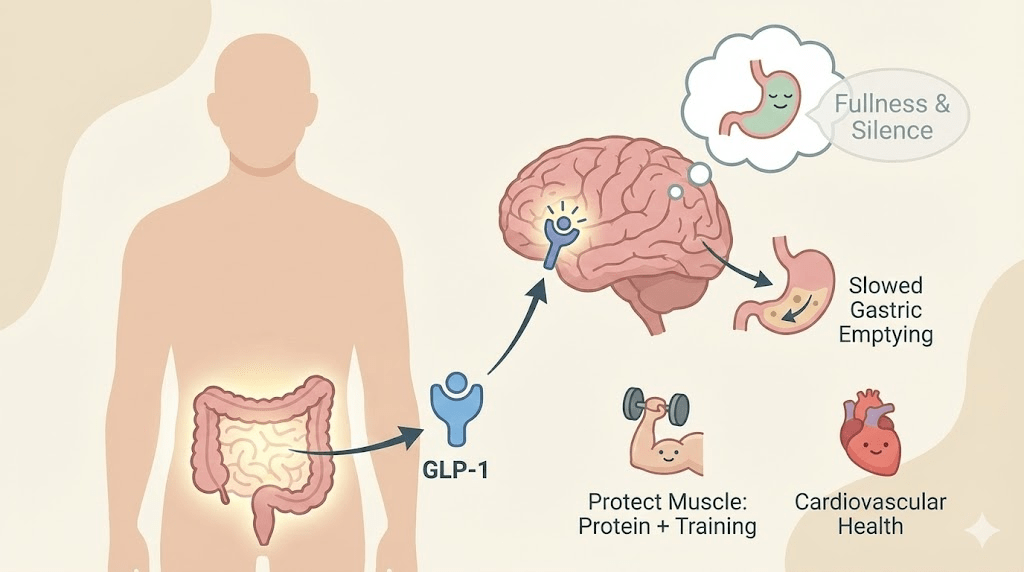

- GLP‑1 is a gut hormone that helps regulate satiety, appetite, and glucose after meals; medications amplify that signal.

- Many people report a reduction in intrusive appetite cues (“food noise”) because GLP‑1 activity influences both homeostatic hunger and reward-driven eating.

- These therapies also slow gastric emptying, keeping food in the stomach longer and extending the physical sensation of fullness.

- Large clinical trials show average weight loss that previously was usually seen only with bariatric procedures, and some trials show cardiovascular risk reduction in high‑risk groups.

- The biggest long-term risk is not “failing” the medication—it’s losing lean mass and under-nourishing the body if protein and resistance training are ignored.

What GLP‑1 is (and why your gut talks to your brain)

GLP‑1 stands for glucagon-like peptide‑1, a hormone your gut releases after eating. Think of it as part of the body’s “meal completed” messaging. It supports insulin release (when appropriate), helps regulate blood sugar, and communicates satiety to the brain.

GLP‑1 receptor agonists are medications that activate the same receptor pathways—often more strongly and for longer than natural GLP‑1—so the satiety signal lasts long enough to change day-to-day behavior. Tirzepatide is slightly different: it activates GLP‑1 pathways and also targets another incretin pathway (GIP), which may contribute to its strong metabolic and weight effects.

Hacking the brain (without relying on motivation)

A major part of GLP‑1 therapy happens in the brain’s appetite and energy-regulation networks, including the hypothalamus. But the lived experience most people describe isn’t “I’m choosing better.” It’s closer to: the volume knob on hunger got turned down.

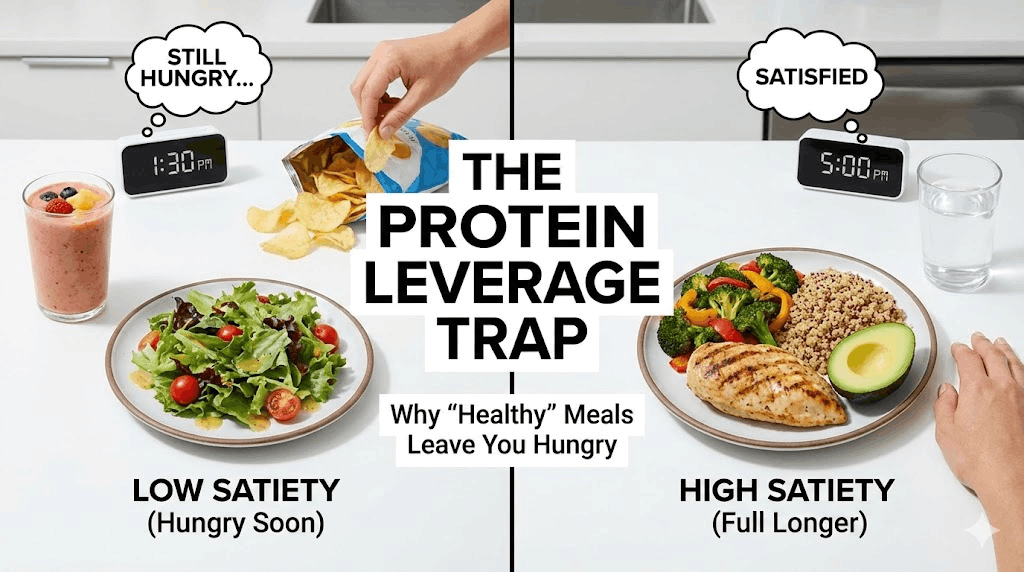

Most people experience hunger in at least two layers: (1) physiological hunger (your body needs fuel) and (2) reward-driven appetite (food as comfort, stimulation, or dopamine). GLP‑1 therapies appear to influence both layers. That’s why many patients report eating smaller portions without feeling deprived—and why certain “trigger foods” lose their gravitational pull.

- Reduced “food noise”: many patients describe fewer intrusive thoughts about food, cravings, and constant planning of the next meal.

- Earlier satiety: the “I’m done” signal arrives sooner, often after portions that previously felt unsatisfying.

- Less reward urgency: food can feel more neutral—still enjoyable, but not compelling in the same way.

The most dramatic effect isn’t willpower. It’s relief—when appetite finally feels quiet enough to make choices.

The traffic jam in the stomach

The second major mechanism is mechanical: GLP‑1 activity can slow gastric emptying. In plain language, food leaves the stomach more slowly. That extended presence sends ongoing fullness signals to the brain and can reduce the urge to graze between meals.

This mechanism also helps explain why overeating on a GLP‑1 can feel uniquely unpleasant. If the stomach is still processing a previous meal, adding extra volume can lead to nausea, reflux, or discomfort. In many cases, side effects are less about “the medication is bad” and more about eating patterns that don’t match the new physiology.

Most GLP‑1 programs use gradual dose escalation to improve tolerability. Early weeks are when nausea, constipation/diarrhea, and appetite changes are most noticeable. Many people adapt over time—especially when meals are smaller, slower, and protein-forward.

Why these drugs changed the obesity conversation

Weight loss is not only about losing fat. It’s also about how strongly the body defends its weight. When weight drops quickly, the body often responds by increasing hunger signals and reducing energy expenditure. That’s one reason why restrictive diets frequently fail long-term even when someone is highly disciplined.

GLP‑1 therapies can blunt that defense by changing appetite, satiety, and eating behavior at the level where the defense is generated—the brain and hormones. This doesn’t make lifestyle irrelevant. It makes lifestyle more feasible.

Benefits beyond the scale

Clinical trials consistently show meaningful average weight loss and improvements in metabolic markers such as blood glucose and insulin sensitivity. But the biggest shift is that these effects can translate into outcomes that matter long-term.

One of the most influential findings is that in a large trial of adults with overweight/obesity and established cardiovascular disease (but without diabetes), semaglutide was associated with a relative reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events compared with placebo. In practice, that means obesity pharmacotherapy is moving from “cosmetic weight loss” into the category of risk modification.

Many patients also see improvements in blood pressure, lipids, and markers tied to cardiometabolic risk. Researchers are actively studying broader effects on inflammation, liver fat, kidney outcomes, and other systems. The field is evolving quickly, but the direction is clear: appetite hormones are becoming a major lever in chronic disease prevention.

The dark side: the muscle paradox

Rapid weight loss can come with a hidden cost: loss of lean mass (muscle and other non-fat tissue). This is not unique to GLP‑1 therapy—it’s a risk with any significant calorie reduction—but it can be amplified when appetite drops sharply and people under-eat protein.

Why it matters: muscle is not vanity. It is metabolic infrastructure. It supports glucose disposal, protects joints, preserves independence with age, and helps keep resting energy expenditure from falling too far. If someone loses muscle while losing fat, they may end up lighter but more fragile, with a metabolism that’s harder to maintain long-term.

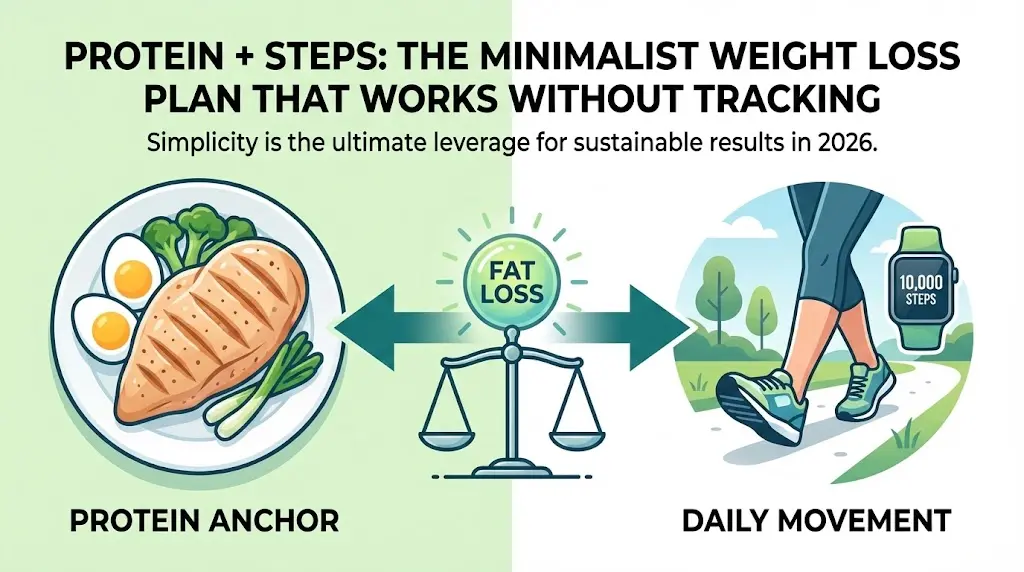

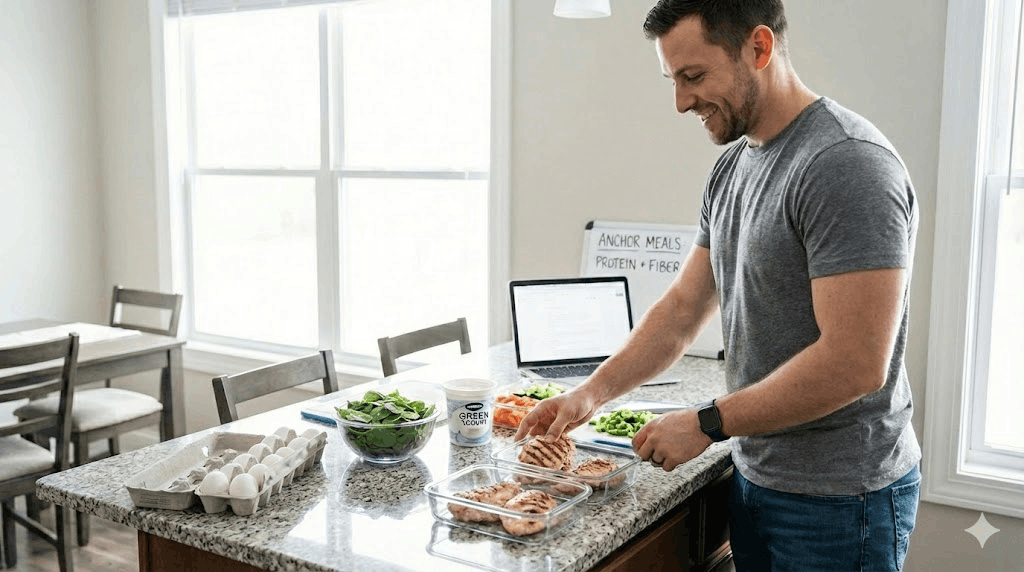

- Protein becomes non-negotiable: prioritize it early in meals, even when appetite is low.

- Strength training is the anchor: 2–4 sessions per week of progressive resistance work is a common target.

- Don’t chase the smallest possible intake: under-eating can worsen fatigue, hair shedding, and muscle loss.

- Hydration and electrolytes matter: nausea and reduced intake can increase dehydration risk.

The goal isn’t the lowest appetite possible. The goal is a body you can live in—strong, nourished, and stable.

Who might consider these medications (and who should be cautious)

GLP‑1 therapies are prescription medications and should be used under medical supervision. They are typically considered when someone has obesity or overweight with meaningful weight-related health risk, especially if lifestyle-only approaches have not produced sustainable results.

They are not appropriate for everyone. Certain conditions require caution or avoidance—particularly a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or MEN2 (as reflected in prescribing warnings), and situations where appetite suppression could be harmful. Any history of disordered eating warrants careful, specialized oversight.

- What is my primary goal—weight, blood sugar, cardiovascular risk, or a combination?

- How will we manage side effects and dose escalation to keep nutrition adequate?

- What protein target and strength plan do you recommend to preserve lean mass?

- Which labs or markers should we monitor (glucose, lipids, kidney function, etc.)?

- What is the long-term plan: maintenance, tapering, or ongoing treatment?

How to use GLP‑1s well: treat it like a system, not a shortcut

The strongest outcomes usually come when GLP‑1 therapy is treated as a platform for habit change: a period when appetite is calmer, cravings are quieter, and routines can be rebuilt. The medication creates opportunity; behavior and environment convert opportunity into durable health.

- Meal structure: 2–3 meals with protein + fiber; smaller portions, slower eating.

- Movement: daily walking plus scheduled strength sessions.

- Sleep: protect 7+ hours when possible; sleep loss increases cravings and reduces recovery.

- Side-effect management: smaller meals, lower-fat options when nauseated, and clinician-guided adjustments.

- Mindset: the win is consistency, not speed.

Common pitfalls

- Eating too little protein because appetite is low, then feeling weak and losing muscle.

- Avoiding strength training and relying only on the scale for “success.”

- Overeating through nausea signals and then blaming the medication.

- Treating the drug as temporary while keeping the same environment that drove weight gain.

- Assuming “no hunger” equals “health,” even when energy, sleep, or mood deteriorate.

Practical next steps

- If you’re on therapy: set a protein-first rule at meals (eat protein before starches).

- Schedule strength work like an appointment (2–4 sessions/week).

- Add a 10–15 minute walk after one meal per day to support glucose control.

- Create a side-effect plan: smaller meals, slower eating, hydration, and clinician check-ins.

- Track outcomes that matter: energy, sleep quality, strength, waist measurement, labs—not only scale weight.

Quick checklist

- Protein target is met most days (or trending upward).

- Strength work is scheduled (not optional).

- Fiber shows up at lunch/dinner.

- Sleep is protected as a recovery tool.

- I’m losing weight in a way that preserves strength, mood, and energy.

Important note: This article is educational and not medical advice. If you are considering GLP‑1 therapy, or already using it, work with a qualified clinician—especially if you have diabetes, gastrointestinal disease, a history of pancreatitis, gallbladder issues, thyroid conditions, or an eating disorder history.