“It’s Not a Furnace, It’s a Hybrid Engine”: The Complete Guide to Metabolic Flexibility and Mitochondria

If you ask the average person what metabolism is, they’ll answer: “It’s the speed at which I burn calories.” If you ask a biochemist, they’ll answer: “It’s the body’s ability to extract usable energy (ATP) from multiple fuels, on demand.” Those definitions aren’t just different—they imply completely different solutions. One leads you to calorie math. The other leads you to cellular machinery, hormones, and the ability to switch gears. This guide explains metabolic flexibility in plain language without diluting the science, and shows how to rebuild the engine that actually determines your daily energy, appetite, and long-term cardiometabolic risk.

Key takeaways

- Metabolic health is largely your ability to switch fuels (glucose ↔ fat) without drama—no dizziness, rage, or constant snacking.

- Mitochondria are the “hardware” that turns fuel into ATP; flexibility depends on how many you have and how well they function.

- Chronically high insulin keeps you locked in sugar-burning mode; the goal is not “zero insulin,” it’s insulin that rises and falls appropriately.

- Zone 2 training is the most reliable way to rebuild fat oxidation capacity; heavy strength work protects the organ that ages fastest: skeletal muscle.

- The best plan is boring: consistent sleep, predictable meals, and low-intensity volume—done long enough for the cell to adapt.

“Metabolism isn’t a calculator. It’s an energy system with multiple gears—and most people are stuck in first.”

Why “Calories In, Calories Out” feels true—and still fails in practice

Calories matter, but they are not a steering wheel. They are a unit of measurement. Your body is not a passive furnace; it actively adapts to stress, sleep loss, food quality, and training load by changing hunger signals, energy expenditure, and fuel preference. This is why two people can eat the same calories and have different outcomes: their hormonal environment and mitochondrial capacity determine what those calories become—glycogen, movement, heat, or stored fat.

- Thermostat vs. calculator: hormones (insulin, cortisol, thyroid hormones, GLP-1, leptin) turn the dial up or down.

- Fuel partitioning: the same meal can be burned, stored, or used to rebuild tissue depending on sleep, stress, and training.

- The real question: can you access stored energy when you need it, or does your brain hit the panic button?

Metabolic flexibility: the “hybrid engine” model

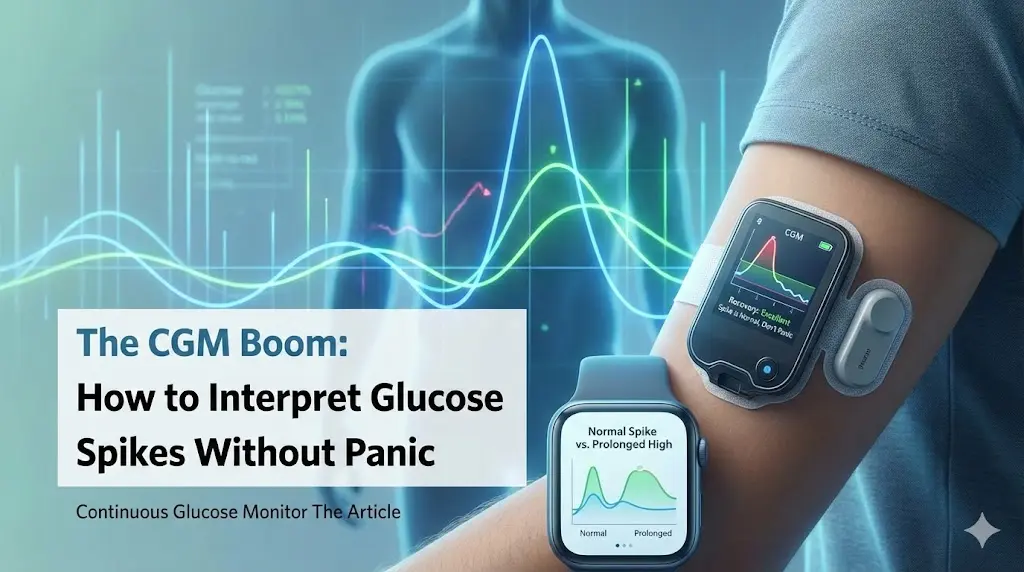

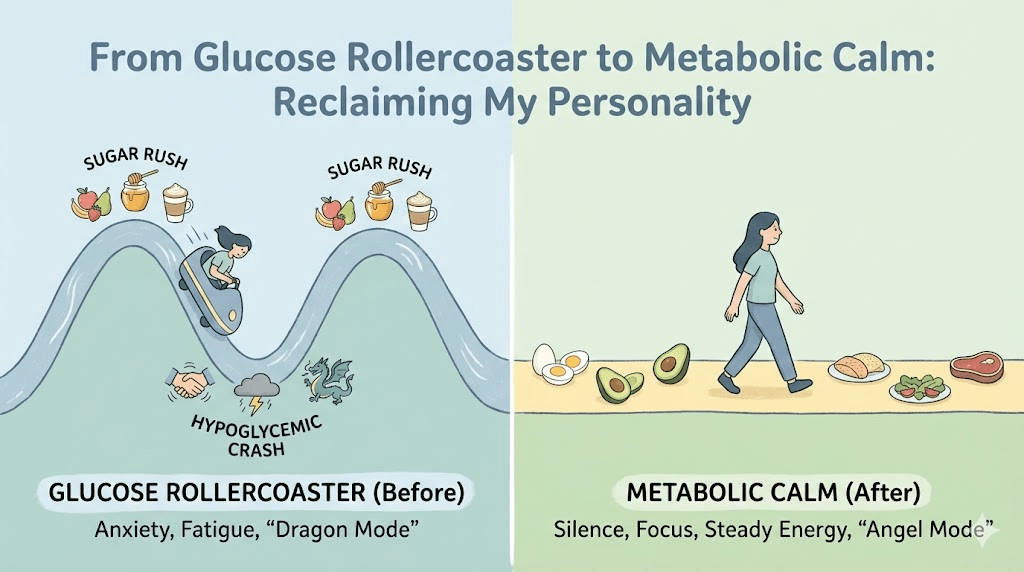

A healthy metabolism behaves like a hybrid car that can smoothly switch between power sources. After a carb-containing meal, you primarily run on glucose. Between meals, overnight, and during easy movement, you should drift toward fat oxidation. Flexibility means the transition happens quietly—without cravings, brain fog, or a “must eat now” emergency signal.

The two engines

- The “gas engine” (glucose): fast, powerful, and perfect for high-intensity work. It relies on glycolysis and a steady supply of carbohydrate-derived fuel.

- The “electric engine” (fat): efficient and long-lasting. It powers low-intensity effort and the hours between meals by oxidizing fatty acids in mitochondria.

When the switch is healthy, you can go from breakfast to lunch without feeling shaky or irritable. When the switch is broken, blood glucose drops slightly and your brain interprets it as danger—even if you have substantial body fat stored.

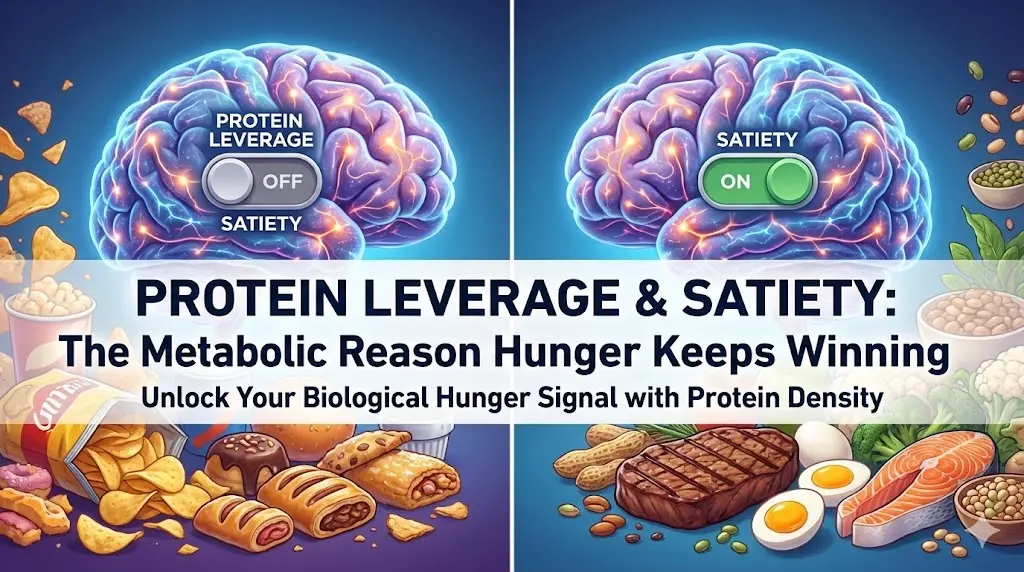

Metabolic inflexibility: what “broken switching” looks like

Metabolic inflexibility is not a character flaw. It’s a predictable physiology created by a modern environment: constant snacking, chronic stress, sedentary time, sleep restriction, and training that spikes stress hormones without enough recovery. The result is a body that relies on frequent glucose input and struggles to mobilize fat when glucose dips.

- You get “hangry” quickly if a meal is delayed.

- You feel wired after sugar, then crash 1–3 hours later.

- You rely on snacks or caffeine to feel normal.

- Cardio feels unusually hard at easy paces (poor fat oxidation).

- You can lose weight short-term but regain easily when you stop “white-knuckle” dieting.

The protagonist: mitochondria (your cellular power plants)

Inside most of your cells—especially muscle cells—are hundreds to thousands of mitochondria. They convert fuel into ATP, the molecule your body uses to do work. Mitochondria are not just “energy factories.” They also signal inflammation, control oxidative stress, and influence insulin sensitivity. When mitochondrial function drops, the entire system becomes less resilient.

Two levers determine mitochondrial performance

- Quantity: more mitochondria = more capacity to burn fat and produce ATP without strain.

- Quality: healthier mitochondria = better fat oxidation, less “leaky” oxidative stress, and more stable energy.

A sedentary lifestyle shrinks both levers. Your body down-regulates unused machinery. You end up with fewer power plants and poorer efficiency, so even small physiological stressors (a missed meal, a bad night of sleep) feel like a crisis.

How insulin locks you into sugar-burning mode

Insulin is not evil; it’s essential. Insulin escorts glucose into cells and helps store energy for later. The problem is chronically elevated insulin—often driven by frequent refined carbs, constant snacking, and low muscle demand. When insulin is high, fat release from adipose tissue is suppressed. In other words: you’re carrying a full fuel tank (body fat), but the nozzle is locked.

- In a flexible system: insulin rises after meals, then returns close to baseline for long stretches of the day.

- In an inflexible system: insulin stays elevated often enough that fat oxidation never becomes the default.

The “overflowing suitcase” problem

Imagine each cell as a suitcase that stores fuel. In a healthy person, the suitcase has space—insulin opens the lid, glucose goes in, and the lid closes easily. In a metabolically stressed person, the suitcase is already overstuffed (excess intramyocellular lipids, high glycogen, chronic surplus). Insulin keeps trying to force more fuel inside. The pancreas responds by producing even more insulin to “shove the lid shut.” That’s hyperinsulinemia—and it’s upstream of many modern metabolic problems.

Why Zone 2 fixes what HIIT often can’t

High-intensity training has benefits, but it is not the best tool for rebuilding fat oxidation. Sprint-style work relies heavily on glucose and creates a large sympathetic stress response. Zone 2—easy cycling, incline walking, steady rowing—forces mitochondria to meet energy demands primarily through fat oxidation. Done consistently, it increases the size and number of mitochondria and improves the enzymes that burn fat.

- Zone 2 definition: you can speak in full sentences, but you’d rather not. Breathing is elevated, control is maintained.

- Why it matters: it trains the “electric engine” and expands mitochondrial capacity.

- Best frequency: modest sessions repeated often beat occasional heroic workouts.

A practical Zone 2 benchmark

If you’re new to aerobic work, start with 20–30 minutes, 3 times per week, and build toward 150–240 minutes per week. The goal is not suffering—it’s volume. You should finish feeling like you could do more. That is exactly why it works: the cell adapts when the signal is repeatable.

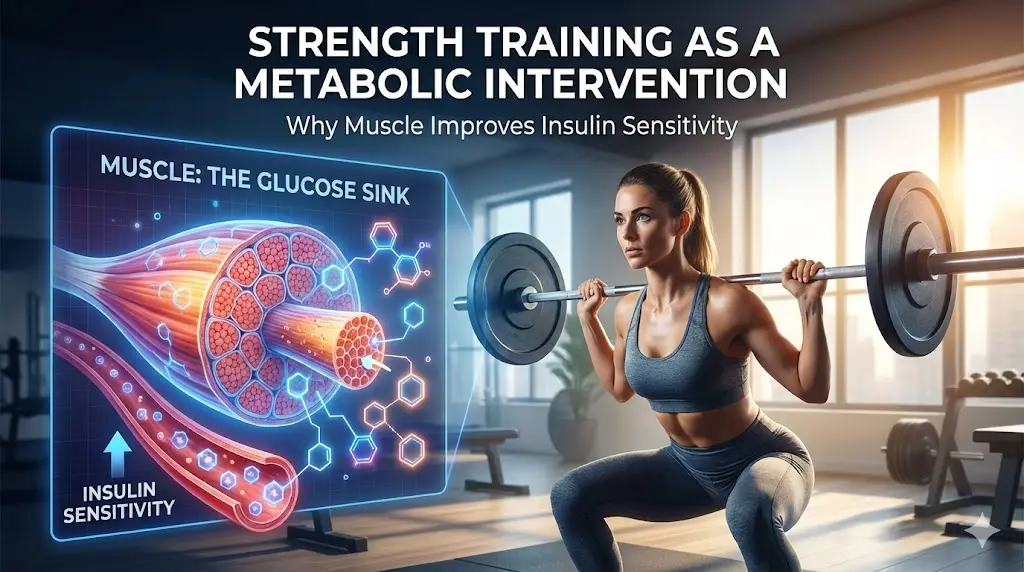

Strength training: metabolic insurance (and the muscle gap)

Muscle is not just for aesthetics. It’s your largest glucose disposal organ and your biggest “buffer” against insulin spikes. More muscle means a bigger glycogen tank and more mitochondrial real estate. Strength training also protects resting metabolic rate during fat loss and reduces the odds of becoming “lighter but weaker.”

- Minimum effective dose: 2 full-body sessions per week (squats/hinges/push/pull/carry).

- Metabolic effect: improved insulin sensitivity and higher storage capacity for carbohydrate without converting it to fat.

- Longevity effect: muscle strength correlates strongly with functional independence as you age.

Sleep: the hidden controller of fuel switching

Poor sleep increases hunger, worsens insulin sensitivity, and increases stress hormones that push you toward quick glucose. Even if you eat “perfectly,” chronic sleep restriction can keep your system inflamed and reactive. If metabolic flexibility is the goal, sleep is not optional—it’s a prerequisite.

- Protect a consistent wake time (even on weekends).

- Keep caffeine earlier than you think you need to (many people feel the benefits after a 10–12 hour cut-off).

- Avoid late-night ultra-processed snacks; they prolong insulin elevation and fragment sleep.

Food strategy: teach the body the switch, don’t shock it

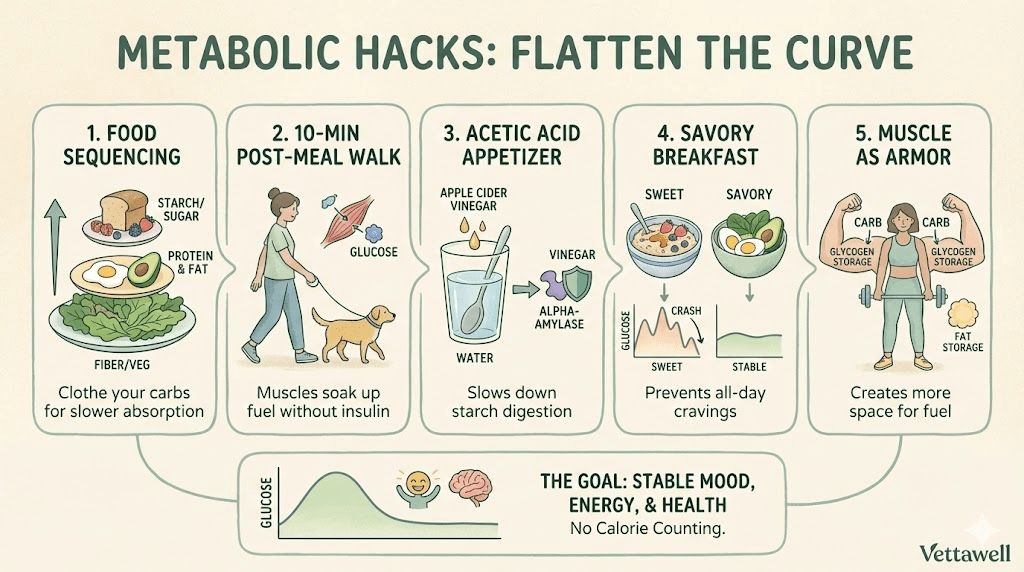

Many people try to “force” fat burning with aggressive fasting or extreme carb cuts. That can work short-term, but it often backfires by increasing stress hormones and binge risk. A better approach is to reduce glucose volatility, reduce constant insulin exposure, and increase muscle demand—so fat burning becomes the default again.

- Meal spacing: 3 meals (or 2–3) with minimal grazing can create real baseline time for insulin to fall.

- Protein first: it stabilizes appetite and supports muscle—the engine you’re trying to protect.

- Fiber and whole-food carbs: improve glucose response without requiring perfection.

How to know you’re becoming metabolically flexible

The body gives early signals long before a scale changes. Look for operational improvements—your “energy system” behaving like a trained hybrid engine.

- You can delay a meal without mood swings or shaky urgency.

- Post-meal energy is stable (no coma, no spike-then-crash).

- Easy cardio feels easier at the same pace (aerobic efficiency improves).

- Cravings become specific and occasional, not constant and compulsive.

- Sleep deepens and morning alertness improves.

A 14-day “rebuild the switch” starter plan

- Pick a consistent wake time and protect it for 14 days.

- Do 3 Zone 2 sessions in Week 1 (20–30 minutes); add a 4th session in Week 2.

- Add 2 strength sessions per week (full-body, simple, progressive).

- Keep meals structured (2–3 meals); remove “default snacking” and liquid calories.

- Make breakfast protein-forward at least 10 of the 14 days.

- Walk 10 minutes after your largest meal on most days.

- Track only 3 signals: 3 PM energy, cravings after dinner, and sleep quality.

When to get help (important)

If you have frequent fainting, palpitations, severe dizziness, unexplained rapid weight changes, or symptoms of hypoglycemia that don’t improve with structured meals, consult a clinician. Endocrine and cardiometabolic conditions can mimic “metabolic inflexibility,” and safety comes first.

Practical next steps

- Choose one lever to start with: sleep consistency or Zone 2 volume. Don’t start with everything at once.

- If weight loss is a goal, prioritize muscle preservation (protein + strength training) before increasing calorie restriction.

- Audit your “invisible insulin spikes”: sweetened coffee drinks, alcohol, and constant small snacks.

- Reassess after 4 weeks, not 4 days. Mitochondria are slow to change—but they do change.

Common pitfalls

- Going too hard too soon (HIIT every day) and driving stress hormones higher.

- Using aggressive fasting as a substitute for aerobic base-building and muscle maintenance.

- Cutting calories so low that training quality collapses and hunger rebounds.

- Tracking weight daily while ignoring waist circumference, strength, and energy stability.

- Assuming “more supplements” can replace sleep, movement, and consistent meals.

Quick checklist

- You do Zone 2 work most weeks (not occasionally).

- You lift 2+ times/week and progress basic movements over time.

- Meals contain protein + fiber, and snacking is mostly purposeful.

- Sleep timing is stable enough that you wake without feeling hit by a truck.

- You can skip or delay a meal without panic, rage, or brain fog.