In popular culture, stress is usually framed as an emotional state—a feeling of being overwhelmed, anxious, or stretched too thin. But in your body, stress is first a physiological cascade: a set of automatic signals designed for short-term survival. It speeds up some systems, shuts down others, and reallocates fuel so you can respond to threat.

The problem isn’t that the stress response exists. The problem is what happens when it runs too often, too long, with too little recovery. When stress becomes chronic, it stops being a useful alarm and becomes a corrosive background process that can change how the brain learns, what it pays attention to, and how the nervous system responds to everyday life.

Chronic stress isn’t a character flaw. It’s a nervous system pattern that can be trained—toward safety, stability, and recovery.

Key takeaways

- Stress is not just a feeling—it’s a body-wide survival program that becomes damaging when recovery is missing.

- Chronic stress can bias the brain toward threat: the “alarm system” gets louder while the “control system” gets tired.

- Inflammation and stress can reinforce each other, affecting mood, energy, sleep, and focus.

- “Rewiring” is really retraining: you build vagal tone, improve recovery capacity, and reduce threat sensitivity over time.

- The fastest improvements usually come from sleep, movement, breathing, and connection—not from willpower alone.

Stress as a survival program (not a mood)

Your stress response evolved for acute danger: a predator, a fall, a sudden confrontation. In those moments, your body needs quick energy, sharper attention, and faster reflexes. The stress response helps by mobilizing glucose, increasing cardiovascular output, and prioritizing threat detection.

But modern stressors are rarely short-lived. A “threat” might be a work inbox, financial uncertainty, chronic caregiving responsibilities, relationship tension, or a nonstop stream of news. The nervous system can’t always distinguish between physical danger and psychological pressure—so it reacts as if it must stay on guard.

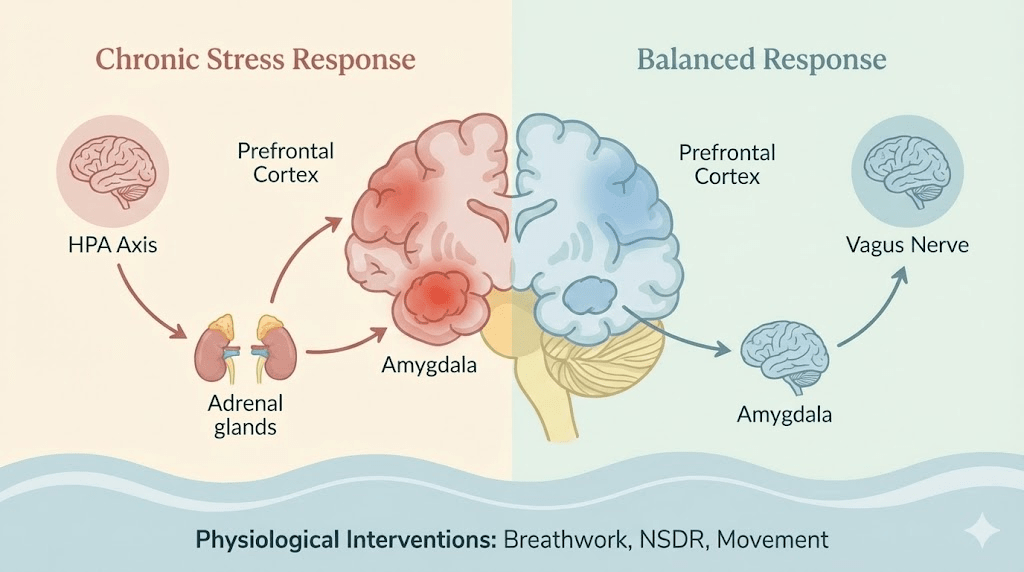

One central pathway is the HPA axis (hypothalamus → pituitary → adrenal glands). When your brain perceives threat, the hypothalamus initiates a hormonal signal that eventually prompts the adrenal glands to release glucocorticoids, including cortisol. In the short term, cortisol is adaptive: it helps you mobilize energy and stay alert.

In a healthy cycle, the system also has an “off switch”—a negative feedback loop that downshifts the response once safety returns. Chronic stress can blunt that recovery loop, keeping the body in a prolonged state of readiness even when nothing urgent is happening.

How chronic stress reshapes the brain

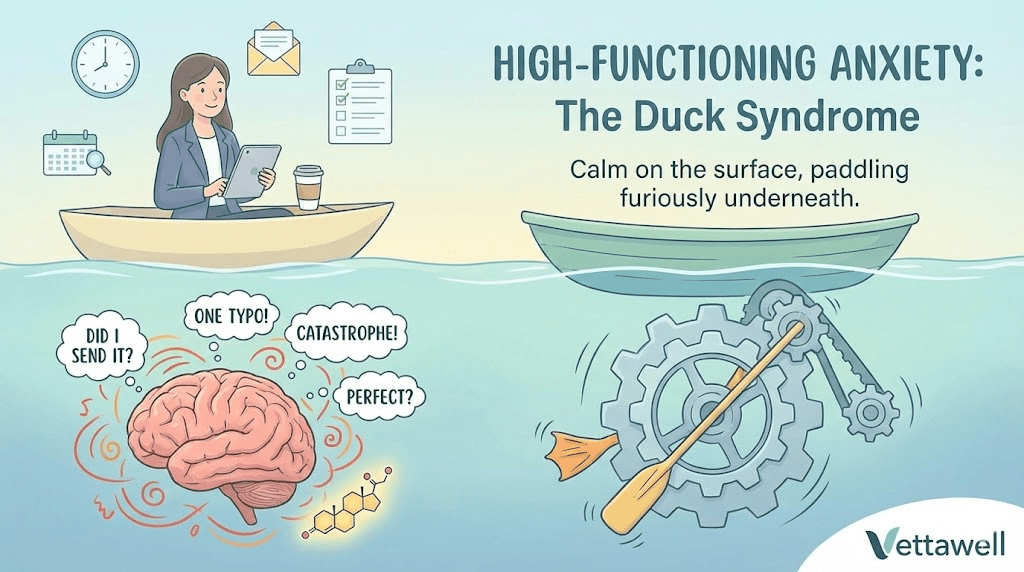

The brain is plastic: it changes in response to what it repeatedly experiences. Chronic stress repeatedly tells the brain, “The world is not safe; stay ready.” Over time, that learning can alter how you think, feel, and focus.

A useful way to understand this is to think in systems. The amygdala is heavily involved in detecting threat and generating fear-based responses. The prefrontal cortex supports planning, impulse control, perspective-taking, and flexible decision-making. Under chronic stress, the balance can shift.

- Threat bias increases: the mind scans for danger, criticism, or what might go wrong.

- Impulse and reactivity rise: it’s harder to pause before snapping, scrolling, or numbing out.

- Focus narrows: attention locks onto urgent tasks while long-term priorities fade.

- Working memory weakens: you forget why you opened the laptop tab, reread the same paragraph, or lose your train of thought.

This creates a vicious cycle: the “brake pedal” (prefrontal cortex) weakens while the “gas pedal” (threat reactivity) gets more sensitive.

This doesn’t mean you are broken. It means your brain is adapting to a signal. The encouraging part is that the same plasticity that amplifies stress can also support recovery—when you consistently train the opposite signal: safety, predictability, and regulation.

Inflammation and the brain

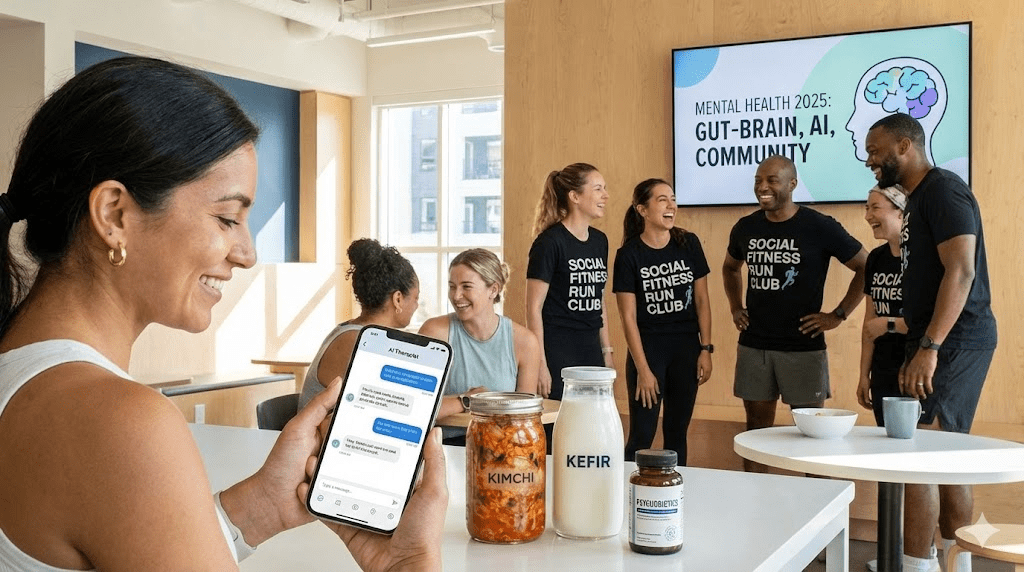

Chronic stress doesn’t only affect the nervous system; it can also interact with the immune system. Under ongoing stress, the body may shift toward higher inflammatory activity. For some people, that inflammatory load is associated with changes in mood, motivation, sleep quality, and cognitive clarity.

Researchers continue to study how inflammatory signaling can influence neurotransmitter pathways and brain function. The practical takeaway is straightforward: if your stress is chronic, your recovery plan has to be whole-body—sleep, nutrition, movement, and stress downshifts all matter because they all change the background physiology your brain is sitting in.

- You’re tired but wired (exhausted, yet restless).

- Sleep is shallow, fragmented, or unrefreshing.

- Small problems feel disproportionately urgent or threatening.

- Digestive issues, headaches, muscle tension, or frequent illness show up more often.

- You crave quick relief: sugar, alcohol, scrolling, shopping, or doom-news.

The vagus nerve: your recovery pathway

If the HPA axis is a major stress engine, the counterweight is the parasympathetic nervous system, strongly associated with vagal pathways. The goal of “stress management” is not to eliminate stress (impossible), but to improve recovery capacity—your ability to shift from activation back into rest-and-digest.

People often describe this as “vagal tone.” In practical terms, it means your nervous system can downshift more quickly after a spike—so you don’t carry yesterday’s stress into today’s conversations, appetite, and sleep.

- Breath patterns that extend exhale: longer exhalations can cue a downshift in arousal. A simple option is two short inhales followed by a slower, longer exhale for 1–3 minutes.

- Non-sleep deep rest (NSDR): guided body scans or yoga-nidra-style sessions can help reduce mental noise and restore a sense of “settling” when traditional meditation feels too hard.

- Optic flow and walking: gentle forward movement (especially outdoors) provides rhythmic sensory input that many people find naturally calming and attention-restoring.

These tools are not “mind over matter.” They are matter—inputs to the nervous system that shift state. They work best when they’re practiced before you’re in a full stress spiral.

Rewiring is repetition, not insight

Most people try to solve stress with insight: understanding the problem, thinking differently, pushing harder. Insight helps, but chronic stress is often a state problem, not a knowledge problem. If your nervous system is activated, the brain will prioritize survival behaviors—even if you “know better.”

Rewiring is really retraining: repeating small regulation practices until the body learns a new default. That might sound unglamorous, but it’s also empowering, because it means progress is measurable in minutes per day—not in perfect life circumstances.

- 1 minute: slow breathing with a longer exhale (count 4 in, 6–8 out).

- 1 minute: unclench—jaw, shoulders, hands; soften your gaze.

- 1 minute: orient to safety—name 5 things you see and one thing you hear; remind your body: “Right now, I’m safe.”

Your nervous system believes what you practice, not what you promise.

Protocols for recovery (a realistic weekly rhythm)

You don’t need a perfect morning routine. You need a repeatable rhythm that pulls you back toward regulation. Think in layers: daily basics, plus a few targeted “resets” during the week.

- Sleep protection: a consistent wind-down cue, a realistic bedtime target, and reduced late-night stimulation.

- Movement: at least one bout of walking or light activity; intensity is optional, consistency is not.

- Protein + fiber: stable meals reduce stress-eating and blood-sugar volatility, which can amplify anxiety for some people.

- Connection: a short, genuine check-in with a friend/partner can be regulating when done without problem-solving.

- One longer NSDR session (10–25 minutes) to downshift mental load.

- One outdoor walk with no audio for at least 15 minutes (let the brain “idle”).

Common pitfalls

- Treating stress like a mindset problem and ignoring physiology (sleep, movement, nutrition).

- Trying to fix everything at once—then quitting when life gets busy.

- Only using tools after you’re already overwhelmed, instead of building them into normal days.

- Confusing numbing behaviors (scrolling, alcohol, overeating) with recovery.

- Expecting to “think your way out” while your body is still in threat mode.

When to get extra support

If stress symptoms are persistent, worsening, or interfering with sleep, work, relationships, or safety, it’s wise to seek professional support. A clinician can help rule out medical contributors (thyroid issues, anemia, sleep disorders, medication effects) and provide targeted treatment. Support is not a failure—it’s a leverage point.

Practical next steps

- Treat stress as physiology: prioritize sleep, movement, and recovery before adding more tasks.

- Pick one rapid tool (breath, NSDR, or walking) and practice it daily for 7 days.

- Add one boundary that reduces stimulation: phone out of the bedroom, news limits, or a late-day caffeine cutoff.

- Do a “stress inventory”: identify your top 3 predictable triggers and decide on a default response for each.

- Track one signal of progress: fewer spikes, faster recovery, better sleep continuity, or less reactivity.

Quick checklist

- I can name my top 3 stress triggers and one response I will use each time.

- I have a 3-minute downshift tool I can do anywhere.

- My sleep routine has at least one consistent cue (same wind-down action nightly).

- I move most days—even if it’s gentle and brief.

- I’m practicing recovery on normal days, not only during crises.