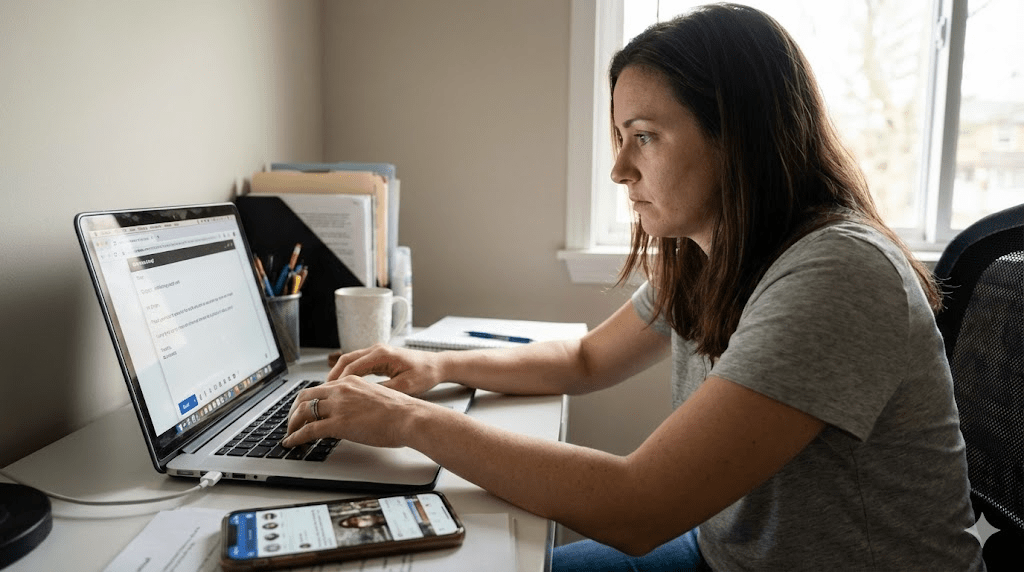

To the outside world, Elena is a machine. At 34, she runs finance like an air-traffic controller: 5:00 AM inbox, immaculate spreadsheets, meetings prepped two days early, and a calendar that looks like a game of Tetris. People call her “disciplined.” What they don’t see is the fuel source: fear. Elena isn’t chasing excellence—she’s running from catastrophe.

High-Functioning Anxiety (HFA) isn’t a formal DSM diagnosis, but clinicians use the term to describe a familiar pattern: anxiety that doesn’t stop you from performing—it drives the performance. It can look like ambition. It can masquerade as high standards. But internally it feels like living with a smoke alarm that never fully turns off.

“It’s like having 50 browser tabs open in your brain, and you can’t find the one playing the music.”

Key takeaways

- High-functioning anxiety often rewards you short-term (deadlines met, praise earned) while taxing your nervous system long-term.

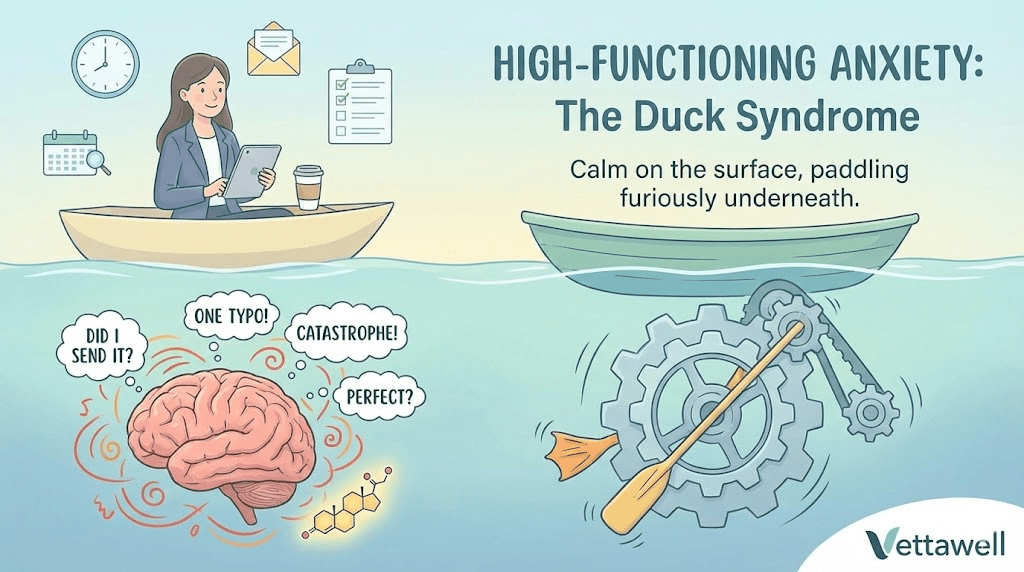

- The “Duck Syndrome” pattern—calm on the surface, frantic underneath—can hide serious burnout risk.

- Anxiety is maintained by safety behaviors (over-preparing, reassurance-seeking, perfectionism) that briefly reduce fear but reinforce it over time.

- The most effective interventions combine cognitive strategies (CBT-style) with physiological downshifts (breath, movement, sleep protection).

- The goal isn’t to eliminate drive; it’s to build a system where performance doesn’t require panic.

What high-functioning anxiety looks like in real life

Elena’s day is full of small rituals that feel “responsible” but function like invisible coping mechanisms. She arrives early to avoid the sensation of being judged. She rereads emails five times to prevent the possibility of being misunderstood. She offers to take on extra work because saying “no” feels dangerous. Each behavior lowers anxiety for a moment—then the brain learns: Good job. That threat was real. Do it again next time.

- Over-preparation: you can’t submit work until it feels bulletproof—even when “good enough” is objectively fine.

- Reassurance loops: asking for confirmation, rereading messages, or checking dashboards repeatedly.

- Achievement anxiety: you succeed, then immediately worry you won’t be able to repeat it.

- Irritability + tight body: jaw clenching, shoulder tension, shallow breathing, frequent headaches.

- Rest guilt: downtime feels like “falling behind,” even when you’re exhausted.

The Duck Syndrome

Psychologists sometimes call this pattern Duck Syndrome: on the surface the duck glides. Underneath, it paddles furiously to stay afloat. The external competence becomes camouflage. Because Elena is effective, people assume she’s fine. And because she’s praised for her productivity, she assumes the anxiety is the price of admission.

The trouble is that you can’t run a human nervous system on adrenaline forever. Eventually the body collects its bill—often through sleep disruption, digestive issues, mood swings, or the classic cycle: sprint → collapse → shame → sprint.

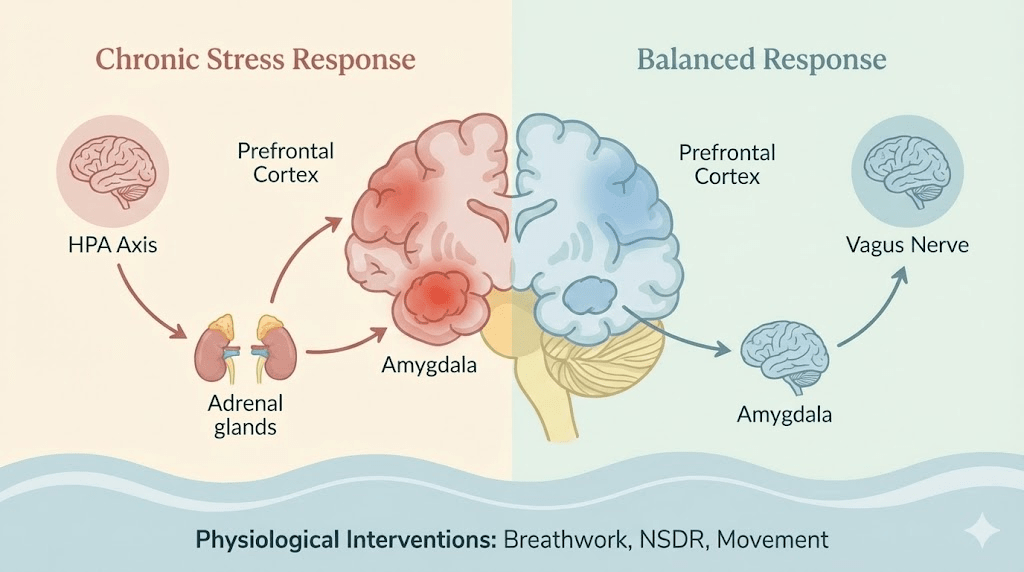

The neuroscience: a brain that won’t go offline

One useful lens is to think in networks. When you’re focused, the brain tends to quiet its self-referential “background processing.” In high-functioning anxiety, that background system stays loud—replaying conversations, forecasting disasters, scanning for mistakes. Even during “rest,” the mind is working.

That’s why advice like “just relax” rarely lands. Relaxation requires a felt sense of safety. Elena’s system has learned that safety equals control, and control equals constant monitoring. So the brain keeps running threat simulations, even when nothing is happening.

HFA is reinforced by a brutal learning loop: anxiety triggers over-effort; over-effort produces success; success becomes proof that anxiety is necessary. Over time, the nervous system pairs achievement with emergency. The result is a high-achieving person who feels strangely unsafe in their own life.

The hidden cost of “being on top of everything”

High-functioning anxiety doesn’t usually look like panic in public. It looks like competence. But the internal cost can be steep—especially when the body never gets enough recovery to reset.

- Sleep erosion: trouble falling asleep (rumination) or waking early (anticipatory stress).

- Decision fatigue: even small choices feel heavy because the brain treats them as high-stakes.

- Relationship strain: partners and friends can feel managed, corrected, or emotionally “held at arm’s length.”

- Physical symptoms: palpitations, stomach issues, muscle pain, frequent illness when stress stays high.

- Burnout risk: productivity spikes followed by periods of shutdown that feel confusing and shameful.

High-functioning anxiety sells you a lie: “If you stop pushing, everything will fall apart.”

The core mechanism: safety behaviors that keep the fire burning

If you want to change HFA, the most important shift is to see the pattern clearly. Many behaviors that feel like “responsibility” are actually safety behaviors—actions you use to prevent a feared outcome. They work short-term, but they prevent the brain from learning that you are safe even without them.

- Over-checking (email, locks, metrics, messages).

- Over-explaining to avoid being misunderstood.

- Perfectionism as protection (“if it’s flawless, I can’t be criticized”).

- People-pleasing to avoid conflict or disappointment.

- Staying busy to avoid feeling vulnerable or uncertain.

The goal is not to become careless. The goal is to reduce the compulsive extras that your anxious brain demands, while keeping the essentials that actually matter.

A practical intervention: the “Worry Time” protocol

A CBT-informed technique that works well for high-functioners is Scheduled Worry (sometimes called Worry Time). It teaches your brain that it doesn’t need to interrupt you all day to keep you safe.

- Capture: when a worry pops up, write a one-line note (“Email might be wrong,” “Meeting will go badly”). Don’t argue with it.

- Postpone: tell yourself, “Not now. I’ll handle this at 5:30 PM.”

- Schedule: set a 15–20 minute daily “worry window” at the same time each day.

- Contain: during the window, read the list and let the worries run. If action is needed, write one concrete next step.

- Close: when the timer ends, stop. If the mind reopens the file later, postpone again.

Most people notice something surprising: by the time the worry window arrives, many worries have lost their charge. Your brain learns that it can be heard without being obeyed immediately.

How Elena started breaking the cycle

Elena didn’t change by “thinking positive.” She changed by building a new operating system: boundaries, recovery, and strategic exposure to imperfection. She proved to her nervous system—through experience—that the world doesn’t end when she stops paddling.

She picked one reliable physiological tool and practiced it when she wasn’t already in crisis. The simplest option: two short inhales through the nose + one long exhale through the mouth, repeated 3–5 times. The goal isn’t bliss. The goal is to bring the system down a notch so the prefrontal cortex can come back online.

Elena chose one low-stakes task per day to submit at 90%. Not sloppy—just not perfect. This is exposure therapy for perfectionism: you allow small discomfort and teach your brain, “I can tolerate uncertainty, and I’m still safe.”

Because her anxiety was rewarded by productivity, Elena treated recovery like a meeting with her most important client. She set a hard stop most nights, kept a short wind-down routine, and stopped using alcohol as an “off switch.” Her output improved because her brain finally had time to rebuild.

Practical next steps

- Write a one-sentence definition of your HFA pattern: “When I feel ___, I do ___ to feel safe.”

- Pick one safety behavior to reduce by 10% this week (one fewer re-read, one fewer check, one fewer “just in case” message).

- Start Worry Time for 7 days: capture → postpone → contain.

- Add one daily downshift tool (breath, walk, stretch) for 5 minutes—practice before you need it.

- Choose one “good-enough rep” per day to retrain perfectionism.

Common pitfalls

- Trying to remove anxiety by force instead of reducing the behaviors that maintain it.

- Confusing rest with laziness and treating recovery as optional.

- Using stimulants or late-night work to override fatigue, then crashing harder.

- Expecting a mindset shift without doing any nervous-system work.

Quick checklist

- Sleep is protected most nights (wind-down routine exists).

- One worry-capture method is in use (notes app, paper list).

- One downshift tool is practiced daily.

- At least one task per day is delivered at “good enough,” not perfect.

- Boundaries exist for work start/stop times.