If you’ve ever watched your child drift through a weekend without plans, you know how fast a parent’s brain can time-travel: They’ll always be lonely. They’ll never fit in. This will shape their whole life. As a parenting author traveling the country, the question I hear most often is also the most heartbreaking: “How can I help my child make more friends?”

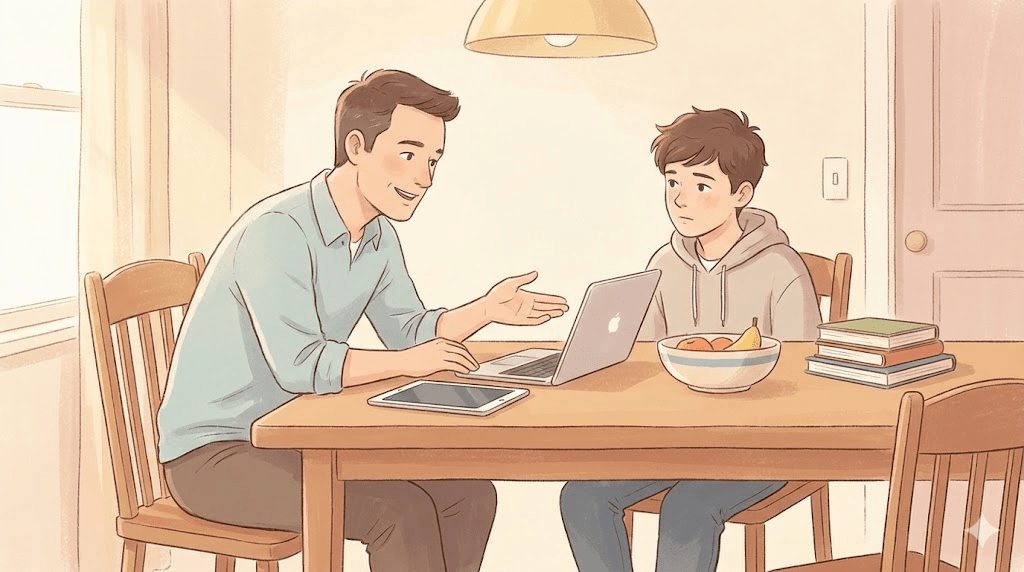

Parents are naturally terrified of social isolation. We see a quiet lunch table or a child staying home as a red flag for a difficult future. And yes—there are practical, supportive things we can do: driving, hosting, snacks, helping kids find activities that match their interests. But the best advice is often the hardest to follow: do less. The outdated maxim that “children should be seen and not heard” is better applied to parents managing children’s social hierarchies: be present, be warm, be a safe base—then get out of the way.

How can I help my child make more friends?

Why parents panic about friendship

Friendship feels high-stakes because it touches identity. When kids struggle socially, parents often feel it as a verdict on their child—and on their own parenting. The anxiety can push us into over-functioning: texting other parents, negotiating playdates like trade deals, and trying to “fix” every awkward moment.

But kids don’t build confidence from having a parent curate their social world. They build confidence from trying, failing, repairing, and learning what connection actually requires: patience, flexibility, humor, and resilience.

The state of modern friendship

To understand why so many parents feel alarmed, I spoke with Sarah Clark, co-director of the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health at the University of Michigan. A recent Mott Poll of more than 1,000 parents of children ages 6 to 12 found a striking number: 1 in 5 parents felt their child had no friends or not enough friends. Only 4% felt their child had too many friends.

Clark notes that this perception often blends what parents hear from their kids with what they infer from behavior—who gets invited, who isn’t, who comes home energized versus depleted. Sometimes parents are right. Sometimes children do have friends, just fewer than a parent imagines is “normal,” or friendships that are quieter and less performative.

- Quantity isn’t the goal. One steady friend can be protective.

- Friendship can be seasonal. Kids rotate groups as interests change.

- Being alone isn’t always isolation. Some kids truly recover through solo time.

The pandemic hangover (and why it affects parents too)

The poll did not show big differences by gender or grade level, and Clark suggests an important root cause: the lingering effects of the pandemic on parents as much as kids. During the pandemic, casual parent-to-parent interactions dropped: hallway chats, sideline conversations, the informal networks where you learn about clubs, sports, birthday parties, and the social “map” of the community.

When parents aren’t plugged into those informal networks, opportunities don’t circulate as easily. Fewer invitations get extended. Fewer carpools get offered. Parents can interpret that as “my child has no friends,” when in reality the infrastructure of social life is thinner than it used to be.

What “seen and not heard” really means

This isn’t about being cold, hands-off, or indifferent. It’s about reducing parental interference inside the child’s peer ecosystem. Think of it as silent support: you create safe conditions, then let kids do the work of connection.

- Be a calm base: greet friends warmly, keep your home predictable, avoid interrogations.

- Lower the stakes: treat friendship as learnable, not destiny.

- Let kids practice: give them chances to invite, host, negotiate, and recover from awkwardness.

Parents can create opportunities, but they can’t make friendships for their kids.

The danger of curating friends

One of the more concerning findings in this space is how easily “helping” turns into selecting. It’s understandable to want your child’s friends to come from families with similar values, routines, or budgets. But Clark warns against crossing the line into identity-based exclusion or coded judgments—discouraging friendships with “those kinds of people.”

That message lands loudly: it teaches children that certain classmates are less worthy of respect or belonging. It also narrows your child’s ability to function in diverse environments—school, sports, work—where they will inevitably interact with people from different backgrounds. As Clark points out, these are classmates, teammates, castmates, future coworkers, and maybe future bosses.

- Focus on behavior, not identity: kindness, empathy, respect, honesty.

- Pay attention to how your child feels after time together: energized, safe, respected.

- Intervene when there’s a pattern of harm (bullying, coercion, exclusion, cruelty)—not when a friendship is merely imperfect.

Model, don’t meddle

So when should a parent step in? Clark draws a clear line between typical conflict and genuine danger. If it’s an argument, resist the reflex to swoop in and solve it. Instead, coach privately. Ask your child what happened, what they wanted, what they said, and what they might try next time.

Your most powerful tool is modeling. Show your children what healthy friendship looks like by the way you handle conflict, apologize, make plans, show up for people, and speak respectfully about others. Kids learn as much from watching your adult relationships as from any direct advice you give them.

- “What do you think they meant?” (perspective-taking)

- “What did you need in that moment?” (needs awareness)

- “How could you repair it?” (repair skills)

- “What’s a small next step?” (reduces overwhelm)

- “Who makes you feel safe and like yourself?” (healthy selection)

When to step in

Doing less doesn’t mean doing nothing. You step in when the situation crosses into safety issues, ongoing cruelty, or patterns that your child can’t navigate alone. The goal is to protect your child while still preserving their autonomy whenever possible.

- Physical danger or threats.

- Bullying, harassment, coercion, or repeated humiliation.

- Signs of serious distress: sleep disruption, school refusal, panic, or persistent sadness.

- Online situations that include adult contact, sexual pressure, or requests for secrecy.

- A friendship that becomes controlling or isolating (your child can’t see anyone else).

Practical next steps

- Create low-pressure opportunities: activities aligned with your child’s interests (clubs, sports, arts, volunteering).

- Become a “logistics parent,” not a social director: rides, snacks, a welcoming home—then step back.

- Encourage one small outreach per week: a text, a invite, a shared activity after school.

- Practice short check-ins instead of long lectures: “Any friend stuff on your mind this week?”

- Rebuild your parent network: one conversation on the sideline, one new contact at school events.

- If your child is stuck, role-play: how to join a group, how to exit politely, how to repair after conflict.

Quick checklist

- My child has at least one place each week to be around peers with shared interests.

- We talk about friendship in a way that normalizes learning and setbacks.

- I’m supporting logistics more than I’m managing outcomes.

- I intervene for safety, not for ordinary discomfort.

- My child knows: they can come to me without being judged or panicked at.