Does this feel familiar? You’re sitting in front of your laptop. You need to write one simple email. You know what to say. You even want to send it. But your body won’t cooperate. Your hands hover. Your brain goes blank. Instead, you grab your phone, scroll, and then spiral into shame: “What is wrong with me? Why can’t I just do it?”

Modern neuroscience and trauma-informed physiology offer a different explanation: sometimes what looks like procrastination is a nervous system state, not a personality flaw. In other words, you may not be lazy. You may be stuck in a freeze response—often called functional freeze when you can still “function” outwardly while feeling internally shut down.

If your body thinks you’re in danger, productivity becomes a luxury.

Key takeaways

- Freeze is a biological survival response. It can show up as numbness, fog, avoidance, and paralysis, even when the task is objectively safe.

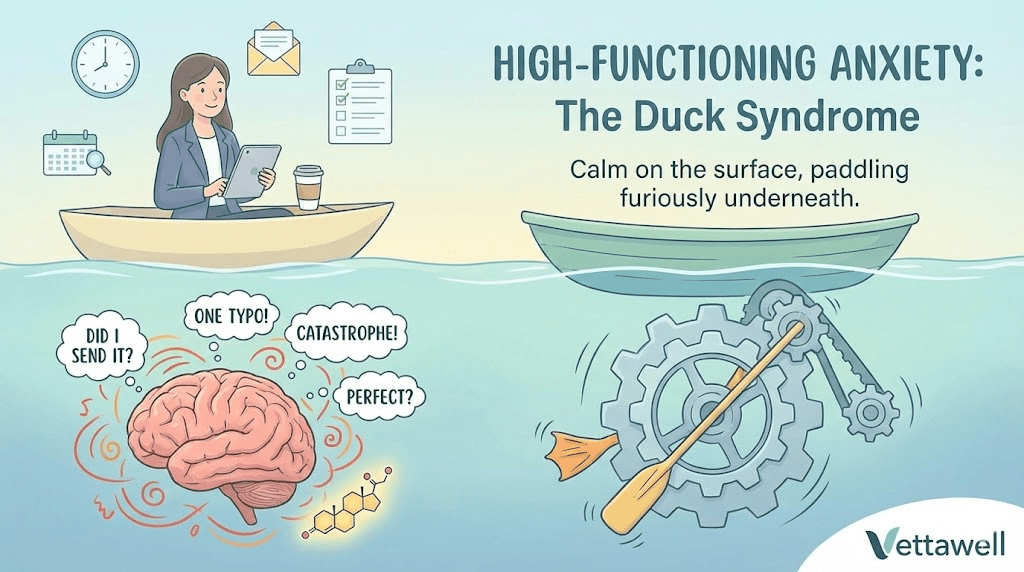

- “Functional freeze” often feels like anxiety + shutdown at the same time: revved engine, locked brakes.

- When you’re frozen, the brain regions for planning and language can become less accessible; you can’t “logic” your way out reliably.

- The fastest exits are usually body-first signals of safety: breath, orientation, movement, temperature, and social connection.

- Progress comes from small, regulated steps (titration), not brute force.

What “functional freeze” actually is

Classic freeze is the body’s emergency brake: when a threat feels too big to fight or flee, the nervous system shifts into immobilization. Functional freeze is a modern variant. You’re not collapsed on the floor—you’re answering messages, going to work, smiling in meetings. But internally, you feel stuck, foggy, or detached, and simple tasks feel enormous.

- You avoid a small task and feel instant relief (then later shame).

- You can do “easy” tasks but freeze on anything with exposure, evaluation, or conflict (emailing, billing, applying, calling, submitting).

- You feel busy but unproductive: lots of movement, very little completion.

- Your body feels heavy, your mind feels noisy, or both.

- You default to soothing behaviors (scrolling, snacking, binge-watching) even when you don’t want to.

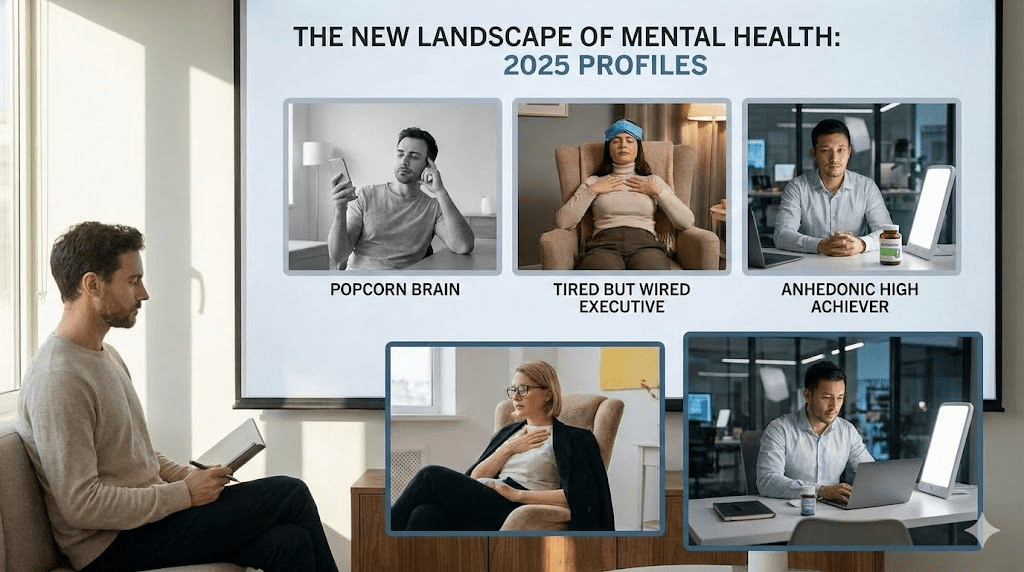

Polyvagal theory: the traffic light model

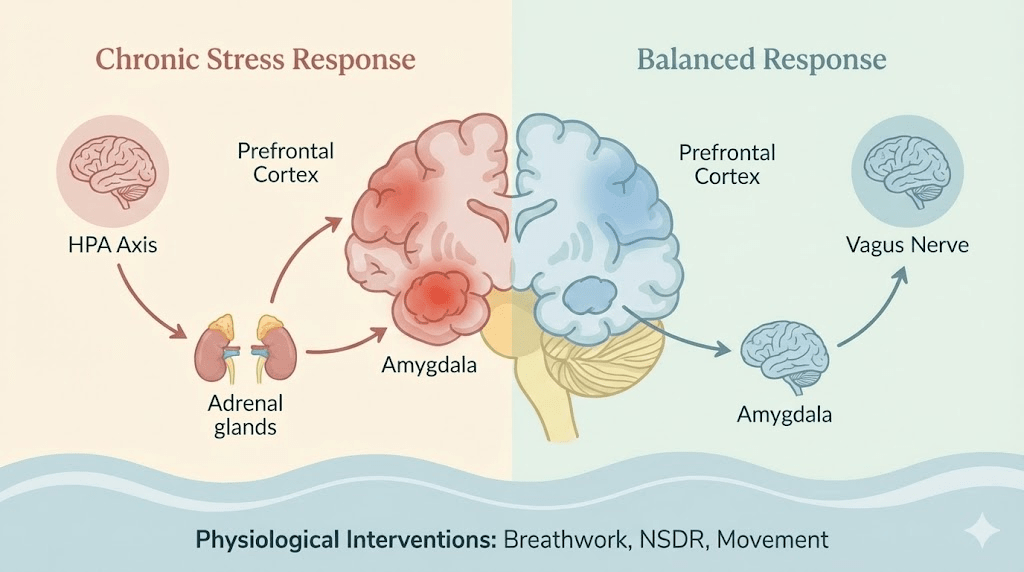

One popular framework for understanding these states comes from polyvagal theory. Whether or not you use the terminology, the practical idea is useful: your autonomic nervous system doesn’t just toggle between “stressed” and “relaxed.” It shifts between multiple modes.

You can think clearly, talk easily, plan, prioritize, and complete tasks. The body feels resourced. Curiosity is available.

Energy mobilizes. You’re alert, vigilant, tense. This can help performance in short bursts, but prolonged activation is exhausting.

The body conserves. Motivation drops. Time feels slow or unreal. You may feel numb, disconnected, or “stuck.”

Functional freeze is often “red + blue”: anxious energy with a shutdown body.

Why your brain won’t “just do it” in freeze

Freeze isn’t a lack of discipline. It’s a protective state. When your nervous system tags a situation as overwhelming, it prioritizes survival over productivity. That can reduce access to executive functions—planning, initiating, sequencing, language, and working memory.

Your nervous system can interpret many modern situations as threats: being judged, disappointing someone, conflict, financial pressure, uncertainty, or “getting it wrong.” The task isn’t dangerous. The meaning attached to the task can be.

- Exposure: “If I send this email, they might react.”

- Evaluation: “If I submit this, I’ll be judged.”

- Finality: “If I choose, I can’t unchoose.”

- Identity threat: “If I fail, it proves I’m incompetent.”

The most common mistake: stimulants and self-attack

When we freeze, we often try to fix it with pressure: extra caffeine, loud self-talk, shame, and urgency. Biologically, that can backfire. If your system is already overwhelmed, more activation can push you deeper into shutdown—like revving a car while the parking brake is fully engaged.

Shame is not a productivity tool. It’s a nervous system threat cue.

How to “thaw” out: speak the body’s language

You don’t need a perfect mindset to begin. You need to change your physiological state enough that action becomes possible. Think of this as shifting from “frozen” to “available.”

Slowly look around the room. Let your eyes land on details. Name a few out loud: “blue chair, window, plant, white mug.” This tells the brain you are present and scanning a safe environment.

Try a simple pattern: inhale normally, then exhale longer than you inhale. Repeat for 60–90 seconds. The goal is not “calm.” The goal is less alarm.

The vagus nerve interfaces with the vocal apparatus. Gentle humming, chanting, or a low vibrating “voo” on the exhale can create a physical signal of safety.

Squeeze your arms firmly, press your feet into the floor, or hold a pillow tightly for 20–30 seconds. Deep pressure input can help the brain map the body and reduce disorganized threat signals.

Freeze is immobilization. Movement—small and safe—can be an exit. Stand up, walk to the door and back, or do 10 slow shoulder rolls. Keep it gentle. You’re signaling “mobilize without danger.”

The “two-minute bridge” method (what to do after you regulate)

Once you feel 5–10% more available, your goal is not to finish the whole task. Your goal is to build a bridge from freeze to action with steps your nervous system can tolerate.

- Open the email draft (that’s it).

- Write one sentence (not the full message).

- Add a subject line and stop.

- Paste a template and close the laptop.

Set a timer for 2–5 minutes. The rule is: you can stop when the timer ends. This reduces “forever” pressure, which is a major trigger for freeze.

Freeze is sticky when your brain doesn’t register progress. When time is up, stand up, exhale, and say: “Done for now.” This trains your system that action does not equal danger.

The nervous system learns through experiences, not lectures.

Why co-regulation works (and isolation often doesn’t)

Humans are social nervous systems. For many people, the fastest route back to the “green zone” is safe connection: a brief call with a friend, working in a shared space, or simply having someone nearby while you start the task. This isn’t weakness—it’s biology.

- Body doubling: work quietly with someone present (in-person or video).

- A 5-minute check-in: “I’m stuck. I’m going to write one sentence.”

- A shared timer: start together, stop together.

What makes freeze more likely

Freeze becomes more common when the nervous system is already depleted. If you’re chronically under-recovered, small tasks can feel like major threats.

- Sleep debt (especially fragmented sleep).

- Under-eating or unstable blood sugar (skipped meals, high caffeine).

- Chronic stress with no recovery (always “on”).

- Unresolved conflict or anticipatory dread.

- Overload (too many open loops, no clear next action).

Practical next steps

- Name it: when you freeze, say “This is a nervous system state,” not “I’m lazy.”

- Do a 90-second downshift: long exhale + orientation.

- Take one micro-action for 2 minutes (open the draft; write one sentence).

- If you re-freeze, repeat regulation before adding pressure.

- Protect recovery: prioritize sleep, movement, and real breaks for 7 days and observe how initiation changes.

Common pitfalls

- Trying to out-think stress while the body remains dysregulated.

- Using stimulants and shame to force output, then crashing harder.

- Waiting to “feel motivated” before taking the first micro-step.

- Treating freeze like a time-management problem instead of an emotion- and state-regulation problem.

- Ignoring persistent symptoms that may benefit from professional support.

Quick checklist

- I can recognize freeze cues (fog, avoidance, numbness, doom).

- I have a 90-second body-first reset I can do anywhere.

- I can shrink tasks into 2-minute actions without negotiating with myself.

- I’m protecting basics (sleep, food, movement) enough to reduce baseline threat.

- If this is chronic or worsening, I’m open to support (therapy, coaching, medical evaluation).

Important note: This article is educational and not medical advice. If you feel persistently overwhelmed, numb, panicky, or unable to function, consider speaking with a qualified mental health professional. If you have thoughts of self-harm or feel unsafe, seek immediate local emergency help.