Mike, a 44-year-old auto shop owner, loved to joke about his gut. He’d slap it like a drum—solid, tight, almost proud of the sound. “That’s not fat, that’s power!” he’d tell his buddies. To him, a firm belly meant he was built like a truck: sturdy, hard to knock down.

Mike didn’t see it as a warning sign because it didn’t look like the soft “spare tire” he associated with being out of shape. His stomach didn’t fold over his belt. It stuck out in a round, tight dome—like a basketball under his shirt. And that specific shape is the one that makes cardiologists pay attention.

A soft belly can be cosmetic. A hard belly is often metabolic.

Key takeaways

- A hard, round belly often points to visceral fat—fat stored deep around organs—rather than pinchable surface fat.

- Visceral fat behaves like a toxic endocrine organ, driving inflammation, insulin resistance, fatty liver, and higher cardiovascular risk.

- You can’t “lipo” visceral fat. The only reliable approach is metabolic deflation: nutrition, movement, sleep, and stress control.

- The most useful tracking metric isn’t just weight—it’s waist size and cardiometabolic markers (blood pressure, triglycerides, glucose/insulin).

- The goal is not perfection; it’s reducing the internal pressure and restoring metabolic flexibility.

Mike’s wake-up call

Mike finally booked a checkup after months of getting winded doing things that never used to bother him: carrying tires, walking up a small flight of stairs, even tying his shoes. He expected a lecture about being “a little overweight.”

Instead, his doctor asked one question that changed the tone of the visit: “Can you pinch an inch on your stomach?” Mike couldn’t. His belly was firm, tight, and resistant—like it was pressurized from the inside.

Hard belly vs. soft belly

There are two broad categories of abdominal fat, and they behave very differently. One is mostly visible and pinchable. The other is mostly hidden and biologically aggressive.

This is the fat you can grab with your fingers. It sits above the abdominal wall. It can be frustrating aesthetically, but metabolically it tends to be less inflammatory than visceral fat.

Visceral fat accumulates beneath your abdominal muscles, inside the body cavity, surrounding organs like the liver, pancreas, and intestines. A belly can feel hard because there’s increased intra-abdominal pressure—like a suitcase stuffed beyond capacity.

If subcutaneous fat is extra padding, visceral fat is internal congestion.

A toxic factory: what visceral fat actually does

Visceral fat is not inert storage. It’s metabolically active tissue that releases fatty acids and chemical messengers that influence the whole body. One reason it’s so dangerous: visceral fat drains into circulation that feeds the liver, so its byproducts can hit the liver repeatedly, day after day.

- Metabolic chaos: Visceral fat releases inflammatory signals that impair how blood vessels function and how cells respond to insulin.

- Insulin resistance: It raises the odds of prediabetes and Type 2 diabetes—even in men who don’t look “obese” by BMI.

- Fatty liver and lipid spillover: Extra internal fat can correlate with fat accumulation in the liver (metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease), worsening triglycerides and cardiometabolic risk.

This is why a hard belly is not just about appearance. It’s often a visible symptom of a deeper pattern: elevated blood pressure, rising fasting glucose, high triglycerides, low HDL, poor sleep, and chronic inflammation.

The anatomy of the lie: why it feels “solid”

Mike assumed firmness meant muscle. His doctor explained that “hard” is often just crowding. The abdominal wall is being pushed outward by internal fat volume and pressure. That pressure can also affect breathing mechanics—making it harder to take deep diaphragmatic breaths—and it can contribute to reflux and sleep disruption.

- Clue #1: you can’t pinch much fat, but the belly protrudes.

- Clue #2: pants size keeps increasing even if weight is “stable.”

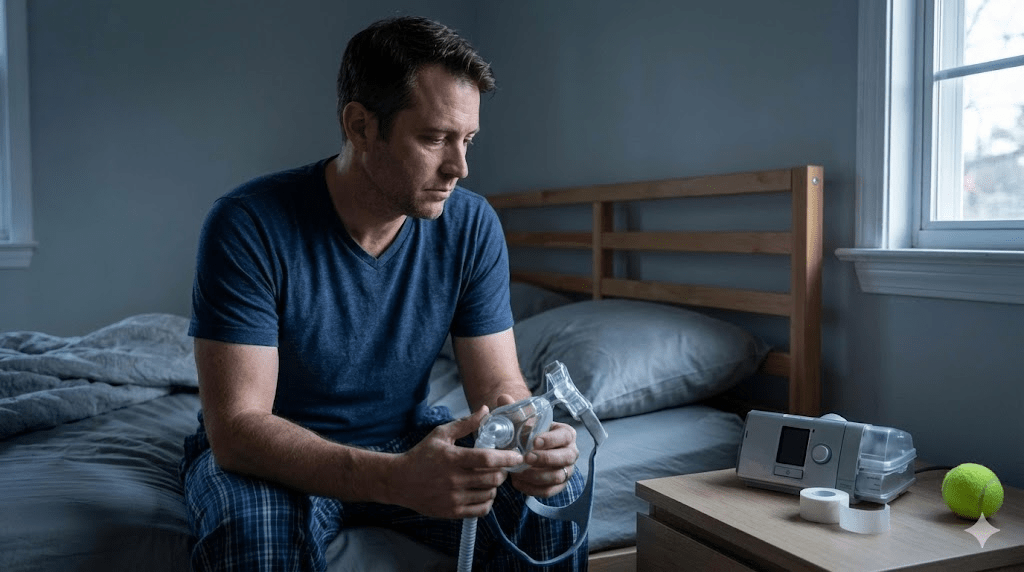

- Clue #3: snoring, daytime fatigue, or waking unrefreshed (visceral fat and sleep apnea often travel together).

- Clue #4: “normal” weight but high blood pressure, triglycerides, or glucose (sometimes called being metabolically unhealthy at a lower BMI).

The liposuction paradox

Mike’s first question was predictable: “Can’t we just remove it?” The problem is that liposuction targets subcutaneous fat. Visceral fat is intertwined around organs—there’s no simple cosmetic procedure that safely “sucks it out.”

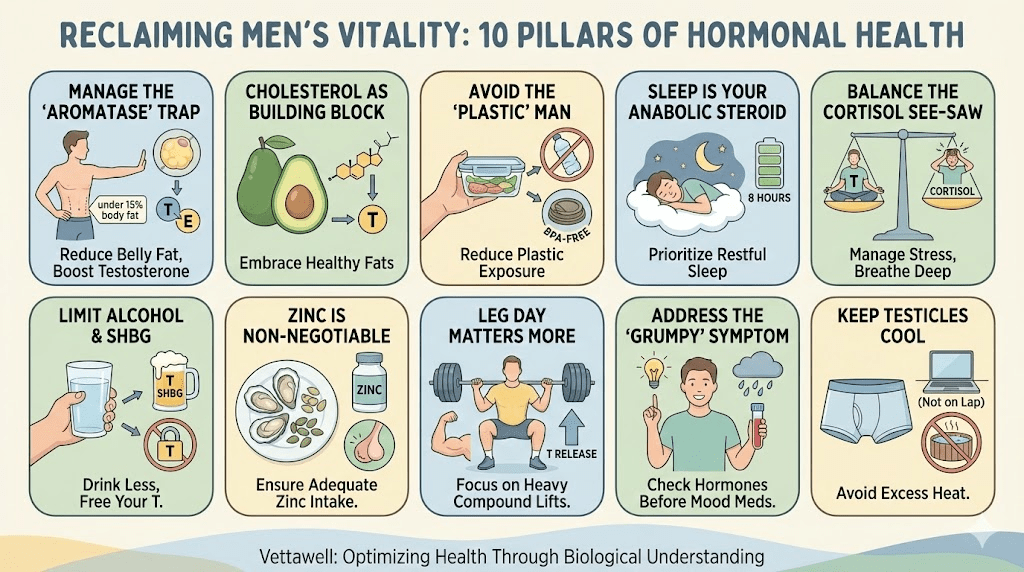

That’s why the solution isn’t surgical. It’s metabolic. Visceral fat tends to respond to lifestyle interventions faster than subcutaneous fat—but only if the plan targets the real drivers: insulin, alcohol/fructose load, sleep debt, and sedentary time.

The deflation protocol

Mike’s doctor framed the goal as deflation: reducing internal pressure, improving insulin sensitivity, and restoring metabolic flexibility. Not a crash diet—an operating system update.

- Liquid calories: beer, sugary cocktails, soda, sweetened coffee drinks.

- Ultra-processed carbs: snacks and refined grains that spike glucose repeatedly.

- Late-night eating: not because breakfast is “bad,” but because constant late intake can keep insulin elevated and disrupt sleep.

Visceral fat is highly sensitive to insulin dynamics. The goal is stable blood sugar and consistent satiety without white-knuckle restriction.

- Protein anchor: include protein at each meal to preserve lean mass and reduce cravings.

- Fiber minimum: vegetables, beans, berries, and whole grains (as tolerated) to support satiety and lipid health.

- Fat quality: emphasize unsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts, fish) and minimize industrial trans fats.

- Alcohol rethink: if you drink, reduce frequency and quantity—visceral fat often shrinks when alcohol intake drops.

Mike liked bench pressing, but strength alone wasn’t enough. The most reliable pattern for visceral fat reduction combines daily low-intensity activity with structured strength training.

- Zone 2 cardio: brisk walking/cycling where you can still talk (aerobic base building).

- Strength training: 2–4 days/week to preserve muscle and improve glucose disposal.

- Post-meal walks: 10–15 minutes after the largest meal to blunt glucose spikes.

You don’t need to train harder. You need to train smarter—and recover like it’s part of the program.

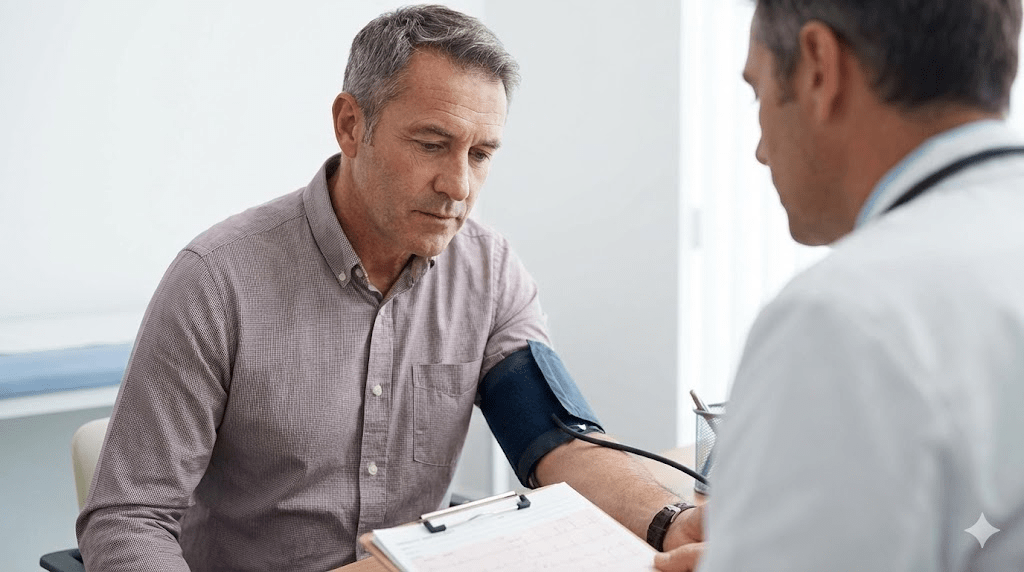

What to measure so you don’t get fooled

Scale weight can lag behind internal improvements. Mike’s doctor told him to track the metrics that visceral fat actually changes.

- Waist circumference: same time of day, same tape position, weekly.

- Blood pressure: at home if possible; trends matter more than single readings.

- Fasting labs (when appropriate): glucose, A1c, triglycerides, HDL, and fasting insulin (interpreted by a clinician).

- Sleep quality: snoring, awakenings, daytime sleepiness—addressing sleep apnea can materially improve metabolic outcomes.

The result

Six months later, Mike’s waist was down several inches. His belly became softer and smaller—not because he “got weaker,” but because internal pressure dropped. He could breathe easier. His energy stabilized. He started walking after dinner instead of collapsing on the couch with a beer.

Mike’s biggest takeaway wasn’t the number on the scale. It was the reframe: a hard gut wasn’t strength—it was a signal.

Practical next steps

- Measure your waist this week and track it weekly for 8–12 weeks.

- Reduce alcohol frequency for 30 days and observe waist, sleep, and cravings.

- Anchor meals with protein + fiber; minimize liquid calories and late-night snacking.

- Add Zone 2 cardio 3–5 days/week plus 2–3 days of strength training.

- If you snore loudly or feel exhausted despite sleep, ask a clinician about screening for sleep apnea.

Common pitfalls

- Chasing ab workouts and ignoring nutrition, sleep, and alcohol intake.

- Assuming BMI equals health and missing metabolic risk at “average” weight.

- Overtraining while under-fueling, which can worsen stress hormones and adherence.

- Trying extreme fasting strategies that backfire via rebound eating or poor sleep.

Quick checklist

- Waist is being tracked weekly.

- Blood pressure is monitored and trending in the right direction.

- Training includes both aerobic base work and strength work.

- Diet includes protein and fiber daily; sugary drinks are rare.

- Sleep quality is improving (less snoring, fewer awakenings, more daytime energy).

Educational note: This article is for informational purposes and is not medical advice. If you have chest pain, severe shortness of breath, or concerning symptoms, seek medical care promptly.