In finance, medicine, law, and tech, the all-nighter is still treated like a badge of honor. But here’s the uncomfortable comparison: if a leader showed up to a critical meeting after a few drinks, it would trigger immediate concern. If they show up after four to five hours of sleep, it often earns applause. From a performance standpoint, the brain doesn’t reward that trade—it penalizes it.

Sleep loss is not just “feeling tired.” It is a measurable form of cognitive intoxication that changes reaction time, emotional control, and risk judgment—exactly the capacities you rely on for high-quality work.

Sleep deprivation is the only impairment that convinces you you’re fine while your performance quietly collapses.

Key takeaways

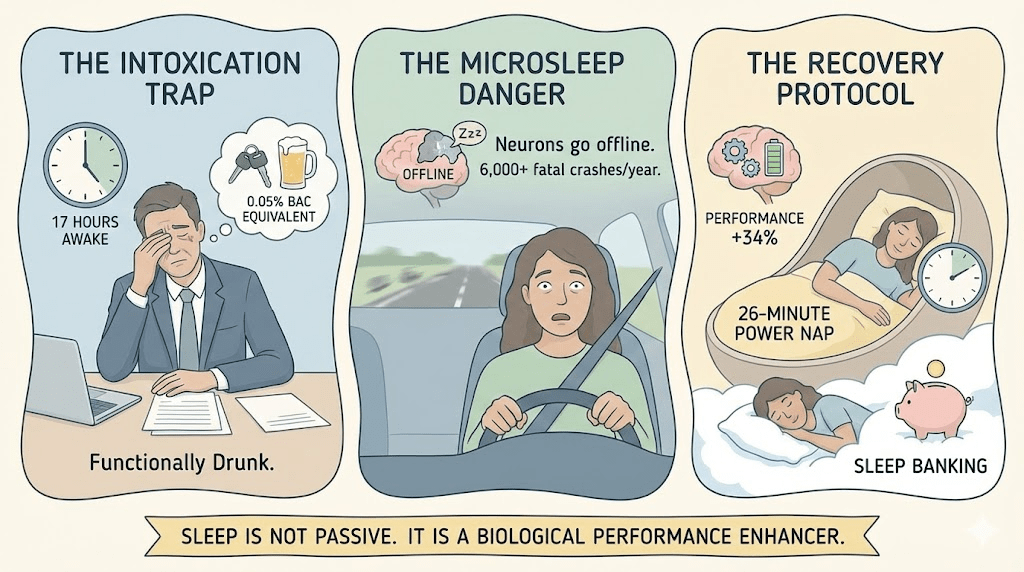

- After roughly 17–19 hours awake, many people perform like they’re at the edge of legal intoxication for driving in several countries—even if they feel “okay.”

- Chronic “not that bad” sleep (for example, ~6 hours nightly) compounds impairment until it resembles severe acute deprivation.

- The real risk isn’t only slow reactions—it’s microsleeps and degraded judgment: you miss details, underestimate danger, and overrate your own competence.

- You can mitigate short-term damage with strategic naps, light exposure, and workload design, but the only true fix is consistent recovery sleep.

The intoxication threshold

Researchers have repeatedly found that staying awake long enough produces impairment comparable to alcohol. A commonly cited benchmark is the “19-hour rule”: once you’ve been awake around 19 hours, your performance on attention and coordination tasks can resemble being legally drunk for driving in many jurisdictions.

Put it into a normal schedule. If you wake at 6:00 AM and you’re still working at 1:00 AM, your brain is operating in a biologically compromised state. You may still type and talk, but your ability to evaluate consequences and detect errors is meaningfully degraded.

- Vigilance drops: you miss obvious issues in spreadsheets, charts, and code reviews.

- Impulse control weakens: you send sharper emails, take bigger bets, and overcommit.

- Working memory shrinks: you can’t hold multiple variables in mind—projects feel “foggy.”

- Threat detection misfires: everything feels urgent, but priorities get scrambled.

The subjective trap: you don’t know you’re impaired

One of the most dangerous features of sleep loss is that self-assessment fails. People often report only mild sleepiness while objective performance keeps sliding. The brain adapts to the feeling of tiredness faster than it adapts to the loss of precision.

This is why teams normalize the pattern. The work still gets done—until it doesn’t. The failure mode is rarely dramatic at first. It’s subtle: one missed detail, one sloppy handoff, one incorrect assumption that snowballs into a costly outcome.

Why accidents happen: microsleeps

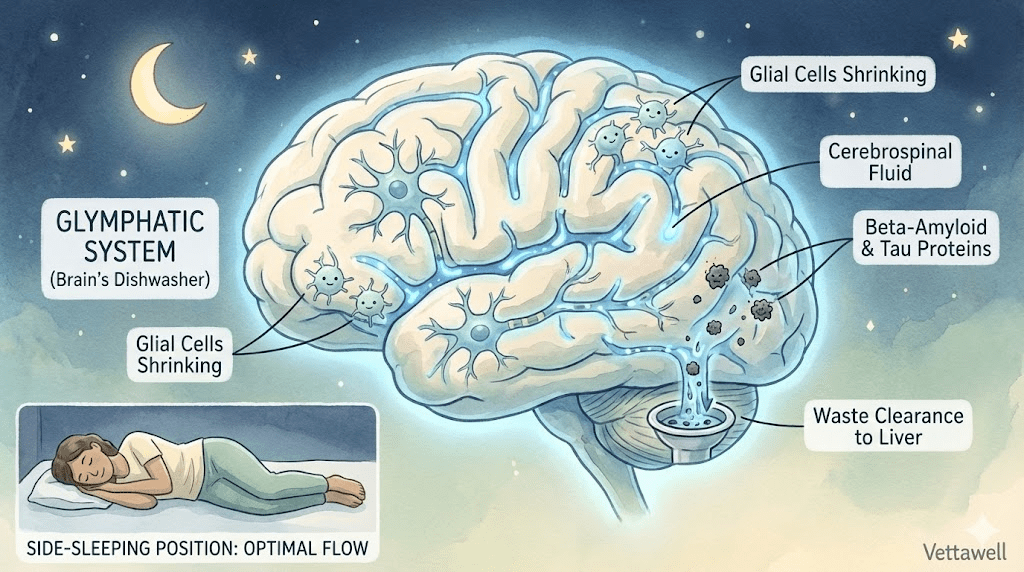

When sleep pressure becomes high, the brain can produce microsleeps—brief moments (seconds) when parts of the cortex go offline. You may look awake, but a portion of your brain is effectively asleep. In a meeting, that looks like losing the thread. On the road, it looks like drifting lanes. In a hospital, it looks like a missed dosage check.

- Microsleeps are more likely after long wake windows, warm environments, and repetitive tasks (driving, monitoring screens, reviewing long documents).

- They are especially risky because they’re often not perceived—people notice the outcome (the mistake), not the moment the brain dipped.

It’s not only slower reactions. It’s missing reality for a few seconds at the worst possible time.

Chronic restriction: the slow-motion collapse

Acute deprivation is obvious. Chronic restriction is the stealth version: you keep sleeping “some,” you keep functioning, and you assume you’ve adapted. But performance keeps eroding beneath the surface.

A practical example: consistently sleeping around six hours can, over time, impair attention and decision-making in ways comparable to much more severe deprivation—while the person reports only mild fatigue. This is why “I’m used to it” is often a warning sign, not a reassurance.

The organizational cost

Sleep deprivation isn’t only a personal health issue. It becomes an organizational risk multiplier: more rework, more conflict, worse prioritization, and preventable safety incidents. Teams pay the tax as friction and error—long before anyone labels it a sleep problem.

- Quality debt: mistakes that require revisiting decisions, rebuilding work, or repairing trust with clients.

- Communication debt: sharper tone, reduced empathy, and conflict escalation under pressure.

- Strategy debt: short-term choices win because long-term thinking becomes neurologically expensive.

Damage control when you can’t sleep (yet)

Sometimes deadlines happen. If you are forced into a short-sleep window, treat it like emergency operations—not a lifestyle. Your goal is to reduce harm and protect the highest-stakes decisions.

Strategic naps can restore alertness and performance temporarily. A short nap (often around 20–30 minutes) tends to improve vigilance without creating heavy grogginess. Longer naps can be powerful, but may cause sleep inertia if timed poorly.

- If you have 15–25 minutes: take a quick nap and get bright light afterward.

- If you have 60–90 minutes: aim for a full sleep cycle (often more restorative), then allow a buffer to fully wake.

- Avoid naps too late in the day if it will sabotage your ability to sleep at night.

- Do not make irreversible decisions in the late-night window (hiring/firing, financial moves, major architectural choices).

- Move critical work to the time of day you are most alert and use the night for low-stakes execution.

- Add friction: double-checks, peer review, and slower send speeds for sensitive emails or approvals.

Sleep banking: the only real performance buffer

If you know a demanding period is coming—travel, launch week, exams—build a buffer in advance. Extending sleep for several nights (and protecting consistency) can improve resilience during the crunch. It doesn’t make you immune, but it reduces the severity of impairment when stress hits.

Practical next steps

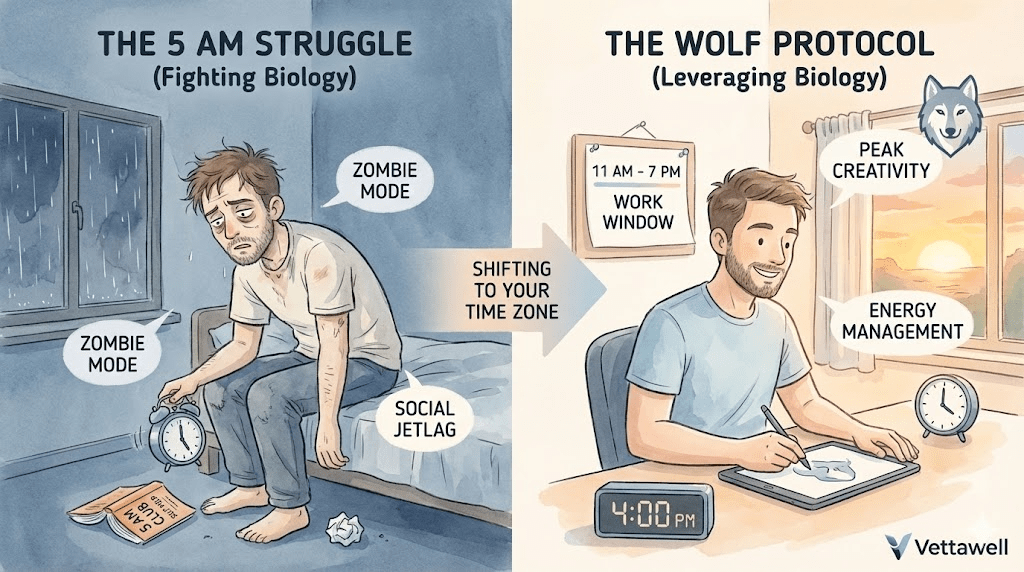

- Pick a non-negotiable wake time for the next 14 days (weekends included) and build bedtime around it.

- Create a 60–90 minute buffer before bed: dim lights, no heavy meals, no work escalation.

- If you must work late, schedule a 20–30 minute nap earlier the next day and avoid major decisions that evening.

Quick checklist

- Wake time is stable (±30 minutes).

- Caffeine cut-off is at least 8–10 hours before bed.

- Bedroom is cool, dark, and quiet.

- High-stakes decisions are not made during late-night fatigue windows.

- A recovery plan exists after deadline weeks (two earlier nights, one low-demand day).