David, a 38-year-old architect, looked like the picture of health. He did CrossFit four times a week, ran 10Ks on Saturdays, and practiced intermittent fasting with near-religious discipline. He had visible abs, a resting heart rate that impressed his friends, and a calendar packed with workouts.

But his body was sending a different report. His libido had faded over six months. He woke up tired no matter how early he went to bed. He felt irritable, flat, and foggy—like his brain was running on low battery. And the most confusing part: despite training hard, he started storing stubborn fat around his midsection.

If your lifestyle constantly tells your body, “resources are scarce,” your biology will respond by cutting anything it can live without.

Convinced he had Low T, David went to a men’s health clinic expecting testosterone injections. He wanted a clean, mechanical fix—like replacing a part. What he got instead was a metabolic reality check.

Key takeaways

- Low testosterone in active men is not always a primary gland problem; it can be a resource-allocation problem driven by stress and under-fueling.

- Chronic high cortisol can suppress reproductive hormones, sleep quality, recovery, and body composition—creating a cortisol-testosterone seesaw.

- Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) can occur in men too, especially with high training volume plus calorie restriction or fasting.

- The so-called “pregnenolone steal” is a useful metaphor: under chronic stress, the body prioritizes cortisol production over sex hormones.

- The most effective intervention is often counterintuitive: eat more, reduce intensity, and rebuild recovery capacity.

The clinic appointment that changed everything

The clinician reviewed David’s labs and didn’t reach for a prescription pad. Instead, he asked questions about training load, sleep, food, and stress. Then he pointed to two numbers that told the real story.

David, your testosterone is low (280 ng/dL), but your cortisol is through the roof. If I give you testosterone now, it’s like putting nitro in a car with a blown engine.

David wasn’t dealing with classic primary hypogonadism. He was dealing with a system under chronic strain: high output, low input, and not enough recovery.

The cortisol-testosterone seesaw

Cortisol is not “bad.” It’s a survival hormone that mobilizes energy and keeps you sharp under pressure. The problem is chronically elevated cortisol—from intense training, poor sleep, life stress, and under-eating. When cortisol stays high, reproductive hormones often get downregulated because reproduction is optional in survival terms.

- Evolutionary logic: In famine or threat, survival beats reproduction.

- Energy economics: Testosterone supports muscle building, libido, and reproductive function—all energy-expensive processes.

- Training stress + low fuel: The brain reads it as scarcity. The body responds by conserving and shutting down “non-essential” systems.

That’s why David had the paradox of the shredded body with the depleted internal state. His outward discipline looked like fitness. Internally, the signal looked like famine.

RED-S: the under-fueling problem most men miss

The clinician used a term David had never heard: RED-S (Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport). It describes a state where energy intake is insufficient relative to energy expenditure—leading to downstream effects across hormones, bone health, thyroid function, mood, sleep, and performance.

David’s pattern was classic: hard training + intermittent fasting + “clean” eating that wasn’t enough for his workload. He was rarely eating in the morning, training intensely on a partial tank, and pushing through hunger as if hunger were proof of virtue.

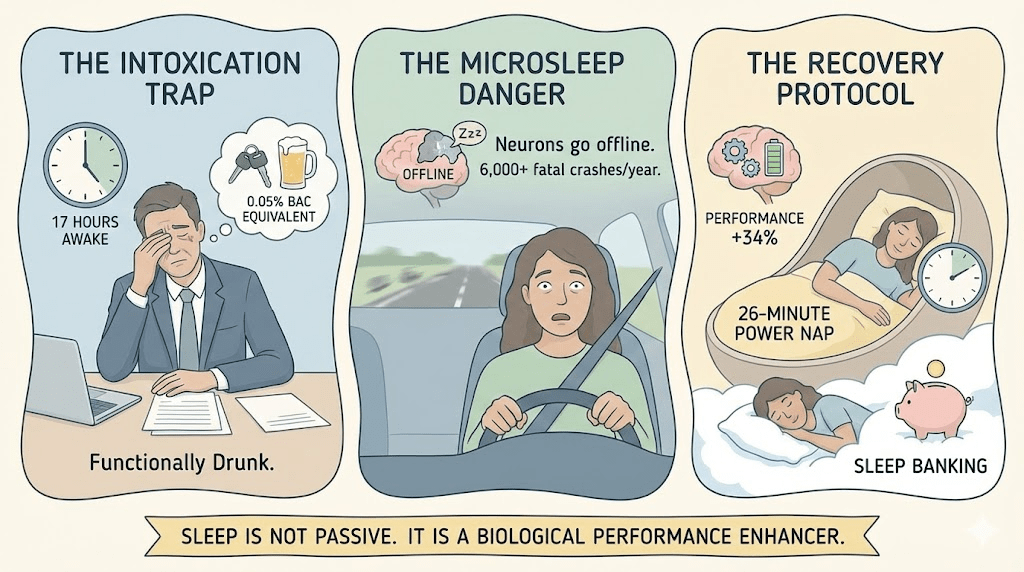

- Sleep feels unrefreshing even when you get enough hours.

- Libido drops or erections become less reliable.

- You feel wired at night, tired in the morning.

- Performance plateaus or injuries become frequent.

- Mood becomes flat, irritable, or anxious.

- You start storing fat despite high training volume.

You can have a six-pack and still be metabolically under-resourced.

The “pregnenolone steal” metaphor

The clinician explained the hormone pathway in plain language. Many steroid hormones begin with cholesterol, which converts into a foundational precursor often described as a “mother hormone.” Under high stress demand, the body prioritizes producing stress hormones—because they keep you alive.

Whether you call it a “pregnenolone steal” or simply stress-driven resource prioritization, the idea is the same: if the body needs more cortisol, it diverts upstream resources away from sex hormones.

- Fasting + intense training: doubles the stress signal.

- Low carbohydrate availability: raises perceived threat during workouts.

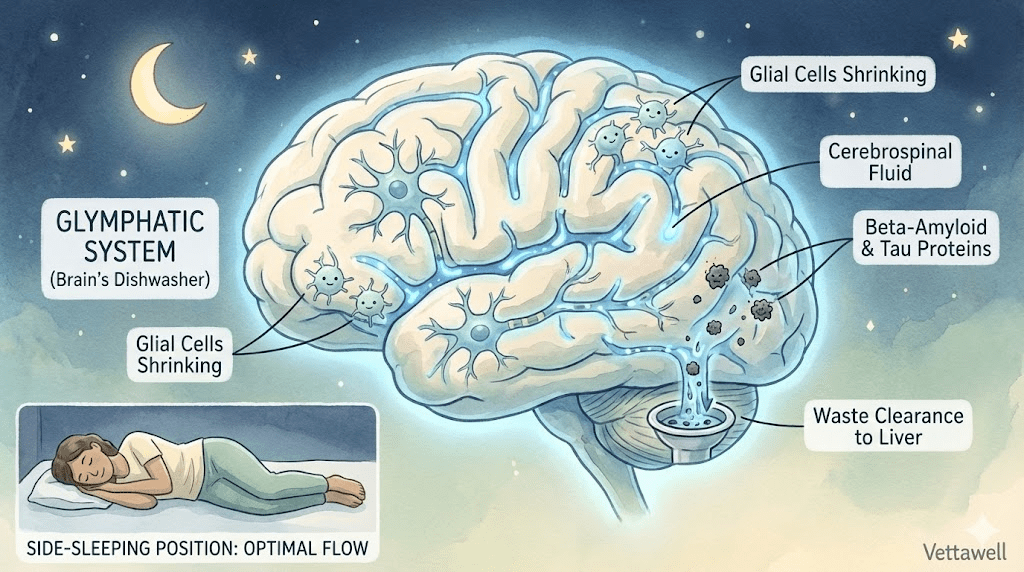

- Poor sleep: reduces testosterone production and increases cortisol.

- High life stress: adds load on top of training stress.

The plan David didn’t want: eat more, do less

The prescription was not a supplement stack. It was a 90-day refueling protocol designed to rebuild safety and recovery capacity. David was terrified of gaining fat. But he agreed to treat it like an experiment: follow the protocol, retest labs, and judge by outcomes—not fear.

- Stop fasting. Eat breakfast within 30–60 minutes of waking to reduce morning cortisol load and re-establish fuel availability.

- Add carbohydrates strategically. Reintroduce complex carbs (rice, potatoes, oats, fruit) especially around workouts to blunt stress response and support thyroid and testosterone signaling.

- Deload training. Reduce intensity and volume: 3 days/week of heavy, slow strength work; no “metcon” finishers; minimal cardio.

- Protect sleep. Aim for 7–9 hours, consistent wake time, and a 60–90 minute wind-down buffer with no work screens.

- Build non-exercise movement. Walking and light activity to support metabolism without additional stress load.

- Track recovery markers. Morning energy, libido, mood, resting heart rate, and training performance—weekly, not daily obsessively.

What happened during the first month

David didn’t feel instantly better. In the first few weeks, he felt puffy and restless—partly from increased glycogen and water, partly from the loss of the workout “high” that had been masking fatigue. He also noticed how much identity he had wrapped around suffering: doing less felt like failure.

The clinician warned him this phase was normal. If your nervous system has been living on adrenaline, calm can feel uncomfortable at first.

The recovery

By month two, David’s mood stabilized. His sleep became deeper. He stopped waking up with that anxious, clenched feeling in his chest. By month three, the most obvious sign returned: morning erections—an old-school, unambiguous marker that his androgen system was waking up.

On retest, his testosterone rebounded naturally to 650 ng/dL. The midsection softness that scared him early on started to reverse once his hormones and sleep normalized. He didn’t become weaker. He became more resilient.

You cannot out-train a starved metabolism. Sometimes the strongest move is to recover.

How to know if you need testosterone—or recovery

TRT can be appropriate for some men, but David’s case shows why it’s risky to assume low T automatically means you need replacement. Low testosterone can be a downstream effect of sleep deprivation, stress load, and under-fueling. Fix the drivers first—then retest.

- Am I training hard and eating in a consistent deficit?

- Is my sleep actually restorative (not just hours in bed)?

- Do I rely on caffeine to function and alcohol to wind down?

- Have I had a deload week in the last 8–12 weeks?

- Do I have persistent injuries, irritability, or mood flattening?

Practical next steps

- Run a 14-day recovery experiment: consistent wake time, no fasting, adequate protein, and reduced training intensity.

- Add carbohydrates around training (especially if you’re doing high-intensity work).

- Schedule deload weeks every 6–10 weeks to prevent chronic stress accumulation.

- If symptoms persist, get labs interpreted with context: testosterone, SHBG, cortisol pattern, thyroid markers, fasting insulin, and inflammatory markers.

- Prioritize sleep and strength work over more volume and more stimulants.

Common pitfalls

- Stacking HIIT/CrossFit volume on top of life stress and calling it “discipline.”

- Using fasting as a badge of honor while performance, libido, and mood decline.

- Cutting carbs so aggressively that training becomes a stress event, not an adaptation signal.

- Skipping deloads and living in a permanent sympathetic (fight-or-flight) state.

- Chasing TRT without addressing under-fueling, sleep debt, and recovery capacity.

Important note: This article is educational and not medical advice. If you have symptoms of low testosterone or chronic fatigue, consult a qualified healthcare professional for proper evaluation and treatment.