Mark, a 34-year-old software architect, lived by a motto he’d absorbed in Silicon Valley: “You can sleep when you’re dead.” His routine was brutal and, in his eyes, impressive. He woke at 4:30 AM to train, drank four shots of espresso by noon, and worked until 11:00 PM. To “wind down,” he had a couple of glasses of scotch and scrolled through emails until he passed out around midnight.

He felt productive. He felt like a machine. And like many high performers, he mistook activity for output. The quality of his attention was slowly degrading, but he compensated by working longer—like turning up the volume to fix a distorted speaker.

You can sleep when you're dead.

Key takeaways

- Sleep debt often shows up first as emotional dysregulation, not yawning.

- Being “unconscious” for 5–6 hours is not the same as getting deep and REM sleep.

- Alcohol can sedate you into sleep while quietly destroying sleep architecture.

- A short protocol (14 days) can meaningfully improve recovery, focus, and output—without “losing your edge.”

- The most reliable productivity upgrade is a repeatable recovery system, not more intensity.

The crash

The breaking point wasn’t dramatic. It was strangely small. One Tuesday morning, Mark found himself crying in his car in the office parking lot because he dropped his keys. He wasn’t sad about the keys. He was experiencing severe emotional dysregulation—a predictable outcome of chronic sleep debt.

Later he told me: “I thought I was fine because I was ‘unconscious’ for five or six hours a night. I didn’t realize being unconscious isn’t the same as recovering.” He finally sought help not because he wanted a softer lifestyle, but because his performance was slipping. He was making coding errors he hadn’t made since he was a junior developer.

- Short fuse: tiny inconveniences trigger outsized reactions.

- Brain fog: rereading the same line, slow recall, scattered thinking.

- Reward seeking: cravings, scrolling, alcohol, or late-night “just one more task.”

- Lowered pain tolerance: everything feels harder than it should.

- False productivity: long hours with diminishing output quality.

The data don’t lie

We put a sleep tracker on Mark, and the results were sobering. While he was in bed for about 5.5 hours, he was getting roughly 20 minutes of REM sleep and almost no deep sleep. He wasn’t recovering—he was sedating himself and sprinting on fumes.

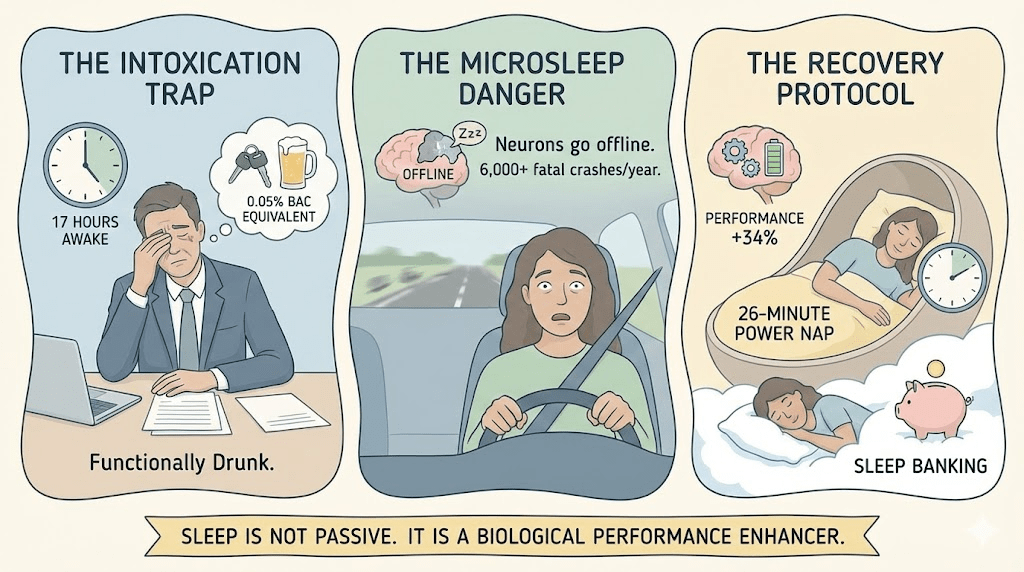

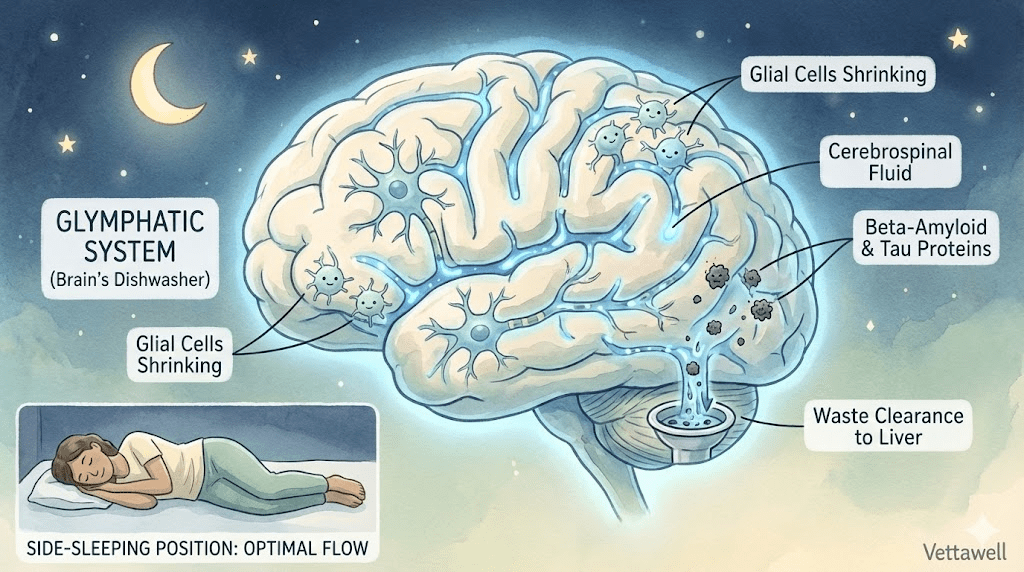

Deep sleep is strongly associated with physical restoration (tissue repair, immune function, metabolic recovery). REM is closely tied to emotional processing, learning integration, and memory consolidation. When REM is short, people often feel “wired and fragile” emotionally. When deep sleep is missing, they feel physically worn down even after time in bed.

- The alcohol trap: Mark believed scotch helped him sleep. In reality, alcohol is a sedative, not a sleep aid. It can fragment sleep and suppress REM—exactly what he needed most.

- The cortisol trap: working until the moment he closed his eyes kept his stress physiology elevated. High arousal makes it harder to downshift into deep sleep.

If your nights are sedated and your days are caffeinated, your nervous system never truly turns off.

The recovery protocol (a 14-day deal)

Mark was terrified that “fixing” sleep would cost him his edge. So we made a deal: run the protocol for 14 days. If his productivity dropped, he could go back to the hustle. The goal wasn’t perfection. It was a measurable change in recovery.

This rule creates a downshift runway so the brain can enter restorative stages more easily.

- 10 hours before bed: no caffeine (Mark switched to decaf after late morning).

- 3 hours before bed: no food and no alcohol (reduce digestion load and protect sleep stages).

- 2 hours before bed: no work (close the laptop; no “one last thing”).

- 1 hour before bed: no screens (reduce cognitive and light stimulation).

To enter deep sleep, the body’s core temperature needs to drop. Mark’s bedroom was too warm. He set the thermostat to about 19°C and took a hot shower before bed. The rapid cooling afterward signaled his brain: night has started.

- Keep the room cool, dark, and quiet.

- Warm shower or bath 60–90 minutes before bed can support cooling afterward.

- If you wake overheated, adjust bedding before blaming “insomnia.”

Instead of checking email immediately, Mark went outside for 10 minutes within an hour of waking. Morning light is a powerful circadian cue. It helps the body build sleep pressure across the day so you feel naturally sleepy at night—without needing alcohol to knock you out.

The part nobody expects: boredom and withdrawal

The first three days were miserable. Mark felt bored and anxious without late-night work and scotch. That discomfort wasn’t random—it was withdrawal from stimulation. When you’ve trained your brain that “nighttime equals intensity,” quiet feels like something is wrong.

So we replaced late-night productivity with a simple wind-down ritual: a low-light shower, a paper book, and a short “brain dump” note with tomorrow’s top three tasks. The point was to stop carrying the whole backlog into bed.

The outcome

By day seven, Mark slept for over seven hours. The tracker showed a meaningful jump in deep sleep. He described it like a hardware upgrade: “It felt like I upgraded my brain’s RAM. I finished a project in three hours that usually took eight.”

Mark didn’t lose his edge. By prioritizing recovery, he sharpened it. He realized sleep wasn’t a passive state of doing nothing; it was an active state of rebuilding—especially for the prefrontal cortex skills he relied on every day: focus, inhibition, and flexible thinking.

High performance isn’t doing more. It’s recovering enough to do the right things well.

Practical next steps

- Set a consistent wake time for the next 14 days (weekends included).

- Pick your caffeine cutoff (aim for 8–10 hours before bed).

- Create a 60–90 minute pre-sleep buffer: dim lights, no work, no heavy meals.

- Replace late-night email with a 3-minute “tomorrow list” (top 3 tasks + one worry you’re shelving).

- Get outside for 5–10 minutes in the morning before screens if possible.

Common pitfalls

- Using alcohol as a nightly sleep tool and confusing sedation with restoration.

- Compensating for fatigue with more caffeine, then needing more sedation at night.

- Trying to fix sleep with supplements while keeping the same late-night work pattern.

- Sleeping in on weekends, then wondering why Sunday night is restless.

- Making the bedroom a second office (emails, Slack, scrolling in bed).

Quick checklist

- Wake time is stable (±30 minutes).

- Caffeine cut-off is at least 8–10 hours before bed.

- Bedroom is cool, dark, and quiet.

- There is a no-work buffer before sleep (at least 60 minutes).

- Morning light happens most days within an hour of waking.